A few weeks ago Artificial Lawyer wrote a piece that contained a line about the need for all lawyers to take legal bots seriously, and that they were going to prove so useful that global firms should be embracing them.

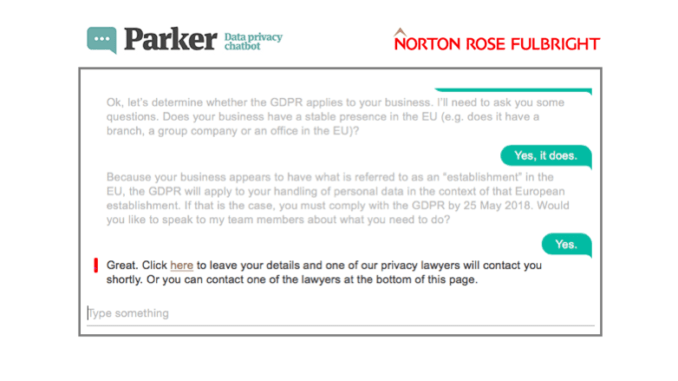

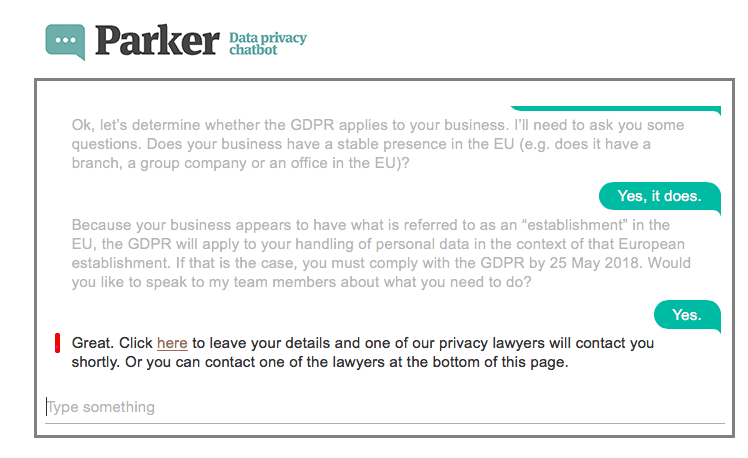

Then, by coincidence, the next day global law firm Norton Rose Fulbright (NRF) announced they had launched a legal bot to help clients with GDPR issues, seemingly proving that Big Law is taking legal bots very seriously indeed.

Artificial Lawyer caught up with Nick Abrahams, the firm’s Global Head of Tech and Innovation, who is a partner in Australia and a driving force behind NRF’s legal bot, Parker, to learn some more.

Abrahams begins the story with the LawPath Alliance, a special platform co-founded by Abrahams separately to the firm back in 2013, which was designed to serve the SME market. LawPath was both aimed at access via fixed-price packages and to operate online.

It perfectly fits the ethos of legal bots, i.e. providing easy to use online facilities that deliver useful legal information and guide non-experts through legal issues.

LawPath showed that there was demand for a solution like this, but the question was whether NRF would want to make one. Abrahams says that initially he had been somewhat doubtful of expert systems – the core idea that legal bots are based on – but that he came around to the idea after seeing how they could be made to respond to natural language.

So, NRF set about creating in Australia the first version of what came to be known as Parker. Parker was built to assist businesses in responding to a major change in Australian law – the introduction of a mandatory data breach notification regime that came into effect on 22 February 2018.

‘We used our internal IT team and we built it very fast, in just six weeks,’ he says.

In the first day it had a thousand interactions. That was back in December 2017. Then in May there followed the release of a new Parker iteration for GDPR in May this year.

And, most recently, last month a Canadian data privacy version was launched, still called Parker, still in effect the same legal bot, but this time designed to handle questions about the mandatory Canadian data breach laws and new regulations that will arrive under the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (PIPEDA) later this year.

In short, Parker has worked so well that it now has versions in Asia-Pacific, North America and Europe. This is certainly a commitment to the use of legal bots.

‘This shows that we can achieve innovation without spending a lot of money,’ says Abrahams.

He adds that now that the wider firm has got to know about Parker there is increasing interest. ‘It’s got global appeal,’ he adds.

Now, before we get carried away, let’s just be clear what an NLP-driven legal bot does. It’s basically a Q&A system that can be client-facing or used internally. It belongs, as noted, to the expert system family of technology. One could say that it is a knowledge-based AI system, rather than a data-driven one. And, probably the use of the term AI here is better left out. It’s easier and more compelling to simply think of a good bot as something that really helps a lawyer or client to learn what they need to know to move along in a legal process, to know their rights, or what the law is, on a particular subject.

It does not give legal advice – you should see the disclaimer under Parker! (See here, scroll to bottom of page.)

Parker and other legal bots, such as those made by LawDroid, or Joshua Browder’s DoNotPay platform, also have to be quite narrow by design. This is because they are ‘pre-set’ systems. If you ask Parker about M&A it won’t have a clue, because it’s designed to ask and answer questions about privacy.

But, conversely, there is nothing to stop Abrahams and team building new versions in different practice areas.

Also, Abrahams notes: ‘This is not replacing a lawyer.’ He adds that in some ways it could be seen as a business development tool, as it encourages companies to seek more detailed legal advice.

He also points out that because it’s based on IBM Watson’s NLP stack it is able to do some machine learning and improve. Though, as mentioned, it is largely still hemmed in by the pre-sets it is designed for.

And could this become a subscription service, like Allen & Overy offers via Neota Logic to its financial services clients? Abrahams says that’s an interesting idea.

So, where is all of this going? Fundamentally, these are early days and Parker probably needs to learn a bit more in its various iterations before it plateaus in that practice area. However, it’s helping the firm to win clients and strengthen relationships, and it’s relatively low cost.

How long before the rest of the firm is using a Parker-type legal bot? It will depend on the use case, but it seems that legal bots may well have a bright future in NRF, at least, and hopefully across Big Law globally. It’s clear that Abrahams believes that legal bots have a bright future.

1 Trackback / Pingback

Comments are closed.