A recent survey of attitudes toward online dispute resolution (ODR) shows that hopes of rolling out such initiatives in the US, UK and other countries face significant challenges – even if the majority of people are in favour of the idea in theory.

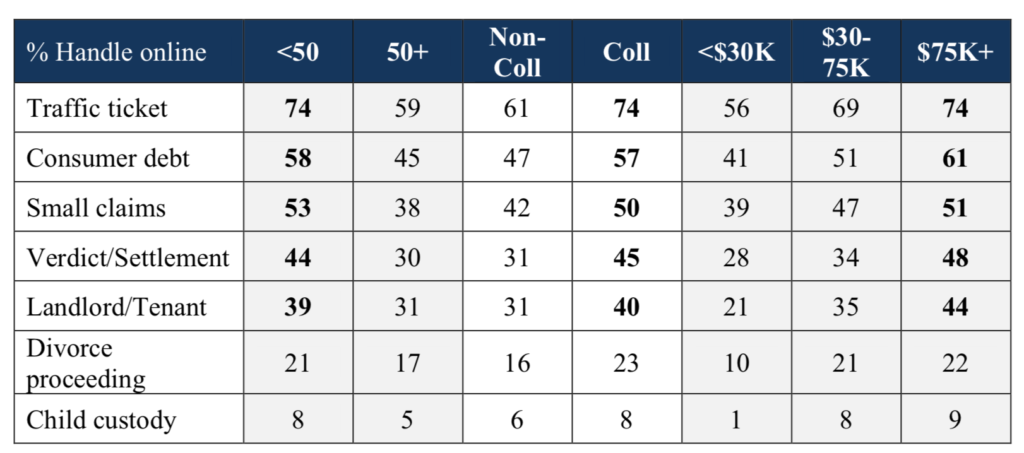

A survey by the US-based National Center for State Courts of 1,000 registered voters developed some of the most fascinated data Artificial Lawyer has seen for a while – please see table 1 below.

So, what does it tell us?

First, although people under 50 are happy to handle a traffic dispute online, when it comes to legal disputes that involve a family member the total plummets.

For example, under 50s saw only 21% willing to engage with an ODR process that handled divorce. And, for the highly emotive issue of child custody that dropped to 8% for those under 50.

If classified just by salary, then those on minimum wages were the least likely of all to use ODR for child custody, dropping to just 1%. This seems to show considerable distrust in the online process for certain types of matter.

The second insight is that the people most likely to be OK with using ODR were under 50, college educated and earning more than $75,000 (£56,500). To some extent we might expect this, i.e. educated, professionals who grew up with the internet are more likely to feel happy with engaging in complex matters online, as, ODR, by its nature demands a high level of proactive engagement from the participants.

That said, even this group were not exactly enthusiastic about handling a matter such as tenancy disputes with ODR, with only 44% of those earning $75,000 likely to want an online resolution.

Moreover, poorer, older and also less educated people generally – according to this survey – seem less willing to engage with ODR. One of the key ideas of ODR is that it will allow disadvantaged people to access justice.

This is not a killer blow, nor stops for example the filing of initial court documents online for divorce, something that is being pioneered in the UK at present, but it does suggest that when it comes to adjudication, many people need convincing and still want to be present in front of a living, breathing judge and to be able to make their arguments directly to that person.

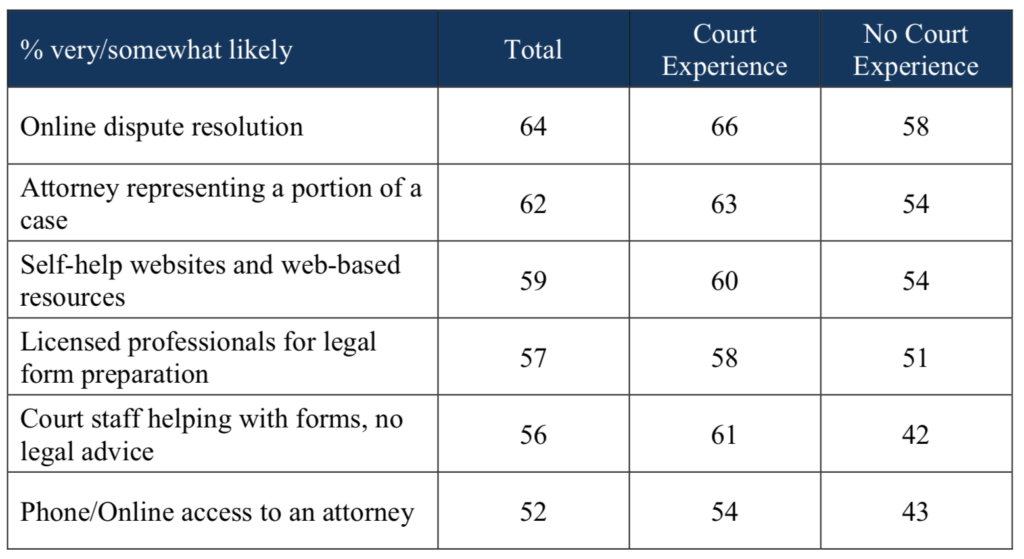

A second set of questions about ways of working with the courts more broadly also showed that people who have already had experience of the courts were more likely to be in favour of alternative approaches, suggesting that perhaps they were not happy with the initial experience and so would try out something new (see table 2).

As seen above, on average 64% of people would try out ODR ‘in general’ – but this has to be seen in context with the results in table 1, i.e. once you start to ask specific questions about what legal issues people would use ODR for, then the number drops rapidly.

Moreover, people who had been to court before were more likely (66%) to want ODR than those who had never been to court (58%).

Surprisingly only 57% of people said they’d like court staff to help complete legal forms, and only 59% on average said they’d like web-based legal resources – one of the key areas of development today with A2J Tech.

I.e. that means even if those resources were online, more than a third of people would not want to use them. Why is this? Perhaps the simple answer is that providing information is not enough, and people want real human guidance, i.e. to be led by someone through the process. Further proof perhaps that the ‘end of lawyers’ is never going to happen.

This is fair enough, but the challenge the US and UK face is a lack of funds to pay for this expert lawyer support, hence a rise in litigants in person.

Commenting on the results, Erika Rickard and Amber Ivey at The Pew Charitable Trusts’ civil legal system modernisation initiative, said: ‘Applied in the court context, ODR allows people to resolve civil legal disputes online without ever setting foot in a courthouse. State and local court leaders are increasingly looking to this approach to modernize and streamline how individuals interact with civil courts and to address the high-volume types of cases that clog their courtrooms’

‘Since the beginning of the year, chief justices in Hawaii, Iowa, Utah, and Texas have highlighted ODR as a key judicial priority in their State of the Judiciary addresses,’ they added.

And, in the UK there is an ongoing effort to explore the benefits of ODR. Although, the above will make potentially interesting reading for the Ministry of Justice and Courts Service.

—

P.S. If you are interested in A2J tech, ODR and litigants in person, then come along to a great fundraising breakfast event organised by The Personal Support Unit (PSU), to be held at the Law Society, 25th March in London: ‘Access to Justice & How the Legal Tech Community Can Help’. For more information about attending the event, please contact: carmen.oloughlin@thepsu.org.uk

All proceeds go to the charitable work of the PSU in helping litigants in person.