By Toni Vitale, partner and head of data protection at JMW Solicitors

The UK Government recently approached O2, Vodafone, EE and Three about using phone signals as part of its efforts to tackle the coronavirus outbreak. The data is anonymised so its use is in compliance with UK and EU data privacy laws, but it may still be an infringement of the human right to privacy under the Human Rights Act. Now there is talk of a NHS app* which can track your recent proximity to anyone who tests positive for Covid-19.

Data regulators, such as the UK’s Information Commissioners Office (ICO), are aware of the struggles organisations and governments are facing in the current Covid-19 pandemic. The ICO has issued a statement to say that provided the data is anonymous, the Government may not be breaching data protection laws. However, the ICO’s anonymity standard is very high – a person must never be able to be identified from the anonymous data. It is doubtful the NHS App can meet this standard.

Take up of the NHS app will need to reach 60% of the population and to be downloaded onto 80% of mobile phones for it to be effective, but if the public accepts this intrusive use of personal data for health reasons in an emergency, are they more likely to accept the UK Government using the data for crime prevention, monitoring large crowds at events, or to replace the national census, due in 2021?

The European Union is likely to take a cautious approach to such monitoring, but in other parts of the world tracking is already taking place. In China, the Government reportedly works with a number of tech giants to keep track of the population. Mass surveillance using apps and mobile technology is already in use in Israel and Hong Kong. The USA is already talking to tech giants, such as Apple and Google, to assist as well.

The European Data Protection Board, which advises the EU Commission on data privacy, advocates a more cautious approach, stating that governments: ‘Should first seek to process location data in an anonymous way… which could enable generating reports on the concentration of mobile devices at a certain location.’

Whilst it recognises that EEA Member States are entitled to introduce legislative measures to safeguard public security, it points out that if this involves non-anonymised location data then the legislative measure must also put in place adequate scrutiny and safeguards. These could include providing the right to a judicial remedy. Yet, in the UK plans are already in motion to curtail the right of judicial review. Blanket surveillance is unlikely to be compliant with EU laws, even when it is ‘for the public good’.

These are extraordinary times, but human rights law still applies. Indeed, the human rights framework is designed to ensure that different rights can be carefully balanced to protect individuals and wider societies. Governments cannot simply disregard rights such as privacy and freedom of expression in the name of tackling a public health crisis.

Human Rights Watch, the international non-governmental organisation, has issued an eight-point declaration to balance individual rights and the need for governments to protect public health:

- Surveillance measures adopted to address the pandemic must be lawful, necessary and proportionate;

- New monitoring and surveillance powers must be time-bound, and continue only for as long as necessary;

- Data must only be used for the purposes of responding to the pandemic;

- Governments must protect people’s data, including ensuring sufficient security;

- Governments must address the risk that the tools will facilitate discrimination and other rights abuses against racial minorities, people living in poverty, and other marginalised populations;

- If Governments partner with private sector entities, the agreements must comply with the law, and sufficient information to allow public oversight must be publicly disclosed. Such agreements should be in writing, with sunset clauses;

- Increased surveillance should not fall under the domain of security or intelligence agencies and must be subject to effective oversight by appropriate independent bodies;

- Data should be shared with relevant stakeholders, in particular experts in the public health sector and marginalised population groups.

The declaration has been signed by many international organisations to urge governments to show leadership in tackling the pandemic in a way that is strictly in line with human rights.

—

About the Author:

Toni has assisted clients on a wide range of privacy and cyber security issues, including regulatory and compliance investigations, data monetisation and data breaches. He has advised on GDPR, e-privacy, PECR, net neutrality, RIPA, reputation management and cyber security. He has consulted with CEOP, the Home Office and NTAC, and has also given evidence to a Joint Committee of Parliament on the Data Communications Bill.

—

[ * AL Note: around the world there is an ever-expanding number of tracing app projects, some of which are already ‘in the wild’ and downloadable now. These are directly backed by governments in some cases, in others they are indirectly supported. Some are on offer in the Apple App Store, and other digital marketplaces, for example one for Singapore, Trace Together, which says it’s backed by the Singapore Government.]

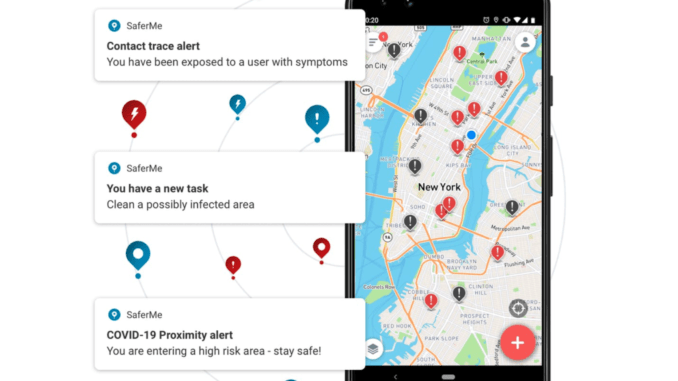

(Main image: a screen shot of a commercial tracing app currently being marketed online.)

– You won’t be able to truly trust the data is “anonymised” or not

– Enough metadata such as location data can be used to identify individuals still

– More data on a person = more ability to control/influence them (case study: Cambridge Analytica)

– The government is probably doing this anyway!