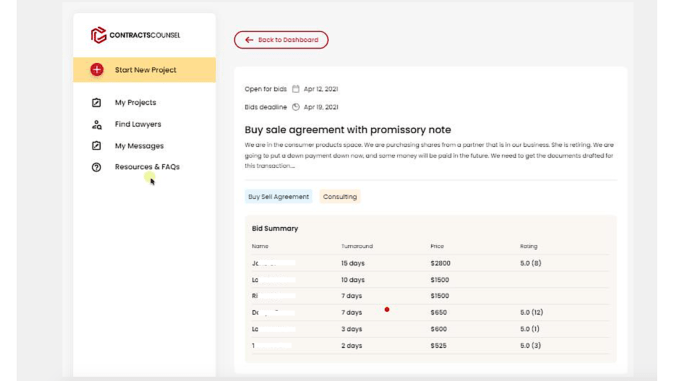

ContractsCounsel (CC) is a marketplace for commercial legal work where lawyers make fixed price bids for mostly contract drafting and review work. It’s also collecting a treasure trove of pricing data that could help support a broader move to fixed fees.

As Founder, Ray Allen, explained to Artificial Lawyer, the marketplace allows a company or individual to make a request for commercial legal help. Mostly solo lawyers then make bids – although some of these are inhouse lawyers who want to do additional work on the side. That in turn has allowed CC to collect pricing data on what frequently demanded contracts should cost.

Eventually they could build a statistical model, i.e. a bell curve chart that showed pricing norms. That in turn could provide some useful benchmarks for the industry, at least in the US.

The data also helps to kill the myth that fixed prices means all buyers taking the lowest offer. See the data below:

‘% represents consumers who did not hire the lowest proposal – number is the total amount of bids for work that lawyers offered to those requesting help.

- All – 44%

- 3+ – 56%

- 4+ – 58%

- 5+ – 67%

- 6+ – 86%’

What this shows is that people don’t pick the lowest offer. As Allen noted: ‘It’s normal behaviour: it’s the wine list. People don’t choose the most expensive, nor the cheapest.’

I.e. the more choice people are given the more they are likely to make a rational decision seeking out the best option at the best price, rather than simply picking the cheapest. Or, alternatively, they also don’t pick the most expensive because of a lack of any other meaningful information as some kind of default position.

As shown, when there were six or more bids made for a piece of work, only 14% of people chose the lowest.

So, that helps to clear up one of the myths about pricing transparency, namely the mistaken idea that giving buyers more information will kill the market.

That said, Allen is well-aware of the challenges the market still faces: ‘[In the legal sector] the producer of the service holds all the cards. They know what you need. We are trying to decouple that, to allow people to comparatively shop for lawyers.’

But back to the fixed price and standardisation of prices. Allen also noted that some lawyers will register with CC not just to gain some additional work, but to find out ‘what is market’. And that is fascinating as it shows that the sellers don’t know what the price should be either.

It’s understandable that buyers can get a bit perturbed that the sellers of legal services are not always being transparent on pricing. But, as noted, the sellers are in the same boat – they also don’t know what things should cost.

As Artificial Lawyer often explores, it’s not that lawyers wanted to build a market that operates like the one we have today – rather it’s an unplanned outcome of the business model of legal services. I.e. lawyers are doing great work, and many clients are very happy with the output, but we’ve all inherited a system that is fundamentally information opaque. It’s evolved this way. But, we also can do something about it.

More clarity is needed. For example, Allen pointed out that their data shows that the price difference for a basic SaaS licence agreement – which was requested by a new software startup – had a range of 10 times the lowest to highest price. In such an opaque market how is anyone – the buyers or sellers – to know what things should cost?

Allen said that the goal now is to bring an end to these ‘huge discrepancies’ and that the ‘normalisation of pricing is an end goal for us’.

To do that they are continuing to gather data to the point where it becomes statistically meaningful. And this is one of the key challenges. If an SME wanted to try and build its own list of fixed prices for what legal work should cost, or ‘is normal’ in their market, they likely would not have enough data to do that.

Larger companies probably could do it for certain external contracting needs that are repeated again and again. They could build a ‘normal curve’, just like Allen is exploring. The challenge is that – as far as Artificial Lawyer knows – large companies are not sharing the pricing data they have for such things, even though they are at liberty to do so.

At the other end of the commercial legal market, Allen and ContractsCounsel are not waiting around to see what happens. They’re building the foundations for pricing transparency.

Last word on this is a very telling anecdote. An ‘expensive lawyer’, as Allen put it, contacted the site to ask why a piece of work that looked especially interesting was on the marketplace. I.e. this is the kind of complex work people like me do, and it shouldn’t be placed in the open like this.

Allen explained that the ‘expensive lawyer’ argued that other lawyers would end up bidding for the matter when they were not sufficiently qualified to do so.

Allen replied that ‘lawyers should know what they can handle’. The site also allows clients to leave feedback on the lawyers that do the work. I.e. it’s transparent.

‘[This kind of attitude] shows the protectionism,’ Allen concluded. ‘They think competition will hurt the market.’

Conclusion

For now, CC is collecting data, but what Allen is finding is that there is a way to build a realistic, fact-based fixed pricing model for the legal world. The challenge, as ever, is that you need the relevant data – and enough of it. Good luck to him.