It’s been popular the last few years for governments to announce big nationwide plans for AI. We’ve seen them in the US, China and the UK. In fact, the UK has just announced a new ‘National AI Strategy’. But do countries really need such top-down plans? And if they do, do they help? Artificial Lawyer explores.

Is AI ‘A Thing’?

Is AI even a thing that you can point at and say: ‘Right! We – as a nation – need a lot more of that stuff, so, let’s get the government involved and utilise taxpayer money to make sure we have enough of it.’

One could argue that AI is not really ‘a thing’ at all. It’s a highly varied, sometimes disconnected array of approaches to analysing data and then trying to make that output into something useful. It’s not an homogeneous area.

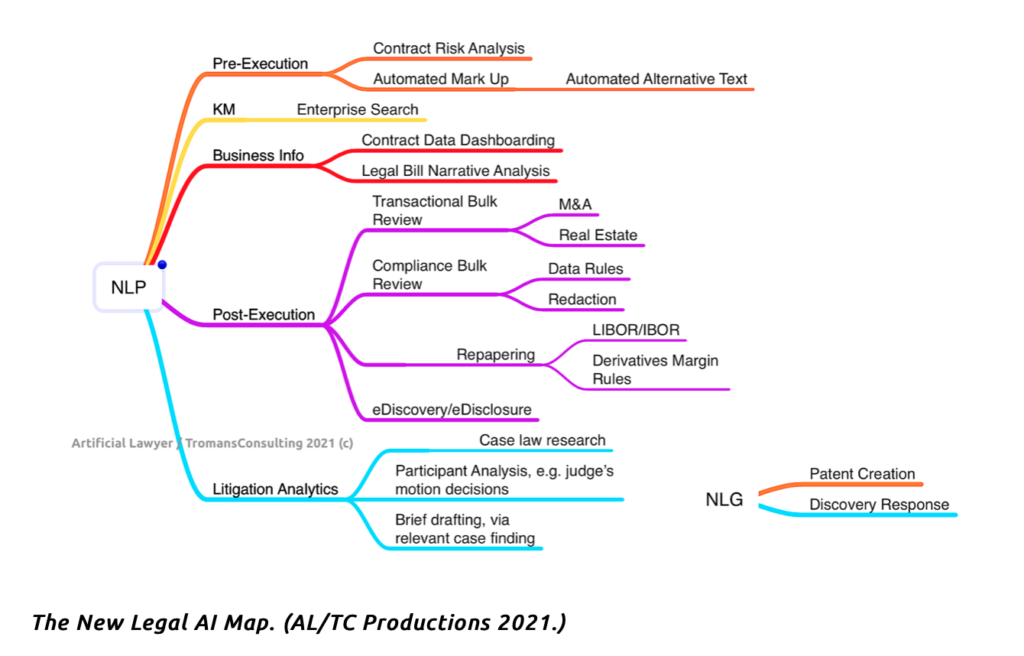

For example, we have many ‘legal AI’ uses – which are themselves very diverse (see image below). And this is just one niche area of the economy. (See: The New Legal AI Map.)

And then there are use cases for:

- Medical analysis, e.g. cancer image review,

- Autonomous driving, e.g. spatial data analysis and response,

- Image search, e.g. using Google when looking for pictures,

- Facial recognition, e.g. the police using machine learning to improve facial analysis of members of the public.

And there are many others. But, as you can see, they are all quite different. Just as if one were to say ‘we need books’ – the response would be ‘OK, which books, what type of books, about what subjects? Do you really mean all books?’

Even the foundational machine learning systems that the various sector use cases need will be different. In the law, it’s all about language and NLP. For Tesla and other car makers it’s all about judging distances to other objects in a highly complex 3-D + time environment. For doctors it’s all about pattern spotting in 2-D static images.

Then there is the entire concept of countries trying to change how economies work from the top down.

E.g. as World War Two started in Europe, the British Government understandably put in place a whole host of measures to ensure there was enough metal to make arms, soldiers were enlisted out of their day jobs, and new workforces were organised to make sure the country didn’t go hungry.

But, is that where we are with ‘AI’? It’s often expressed as some kind of national security issue, and we often are told that we are falling behind X country, or doing better than Y country in terms of AI, as if that was even measurable in any objective way – especially when a whole load of ‘AI software’ can be downloaded for free from open source websites no matter where you are in the world.

Moreover, inventions related to machine learning then go worldwide. Google operates globally. So does Tesla. And most legal tech companies selling NLP-based products would presumably sell into any market globally.

Is there really an ‘AI arms race’ as it’s often put? Maybe between private companies and perhaps between the security agencies of different nations, but broadly for most people there is no sense of some kind of ‘AI Death Match’ in action. There’s just stuff they use, such as Google.

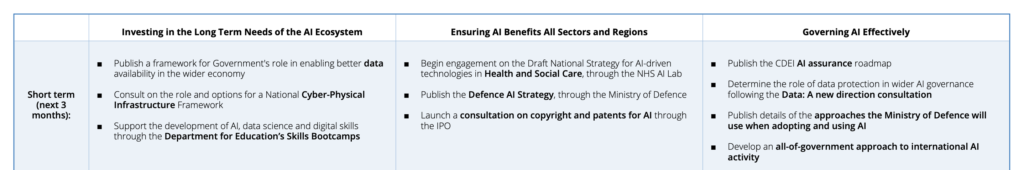

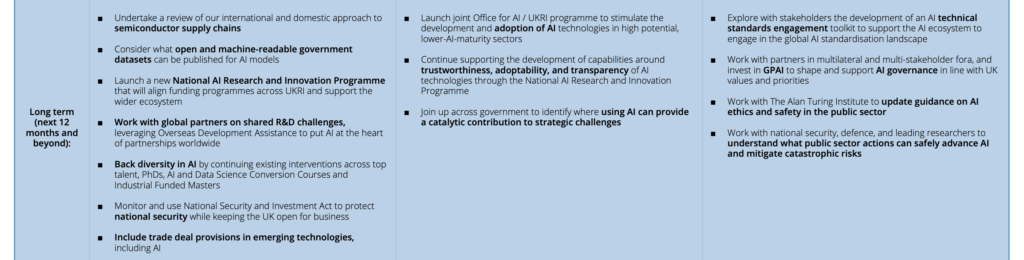

The AI Plan

The UK’s AI plan is divided into three timelines, short, medium and long term, (see below – you may need to expand the page to read in detail).

There’s a lot of things around education and making sure bright AI experts stay in the UK. And there is one easy way to do that: pay them more money than they get elsewhere – and that’s not really something the Government can do much about when it comes to private companies.

Where there does seem to be something the Government can do – but again only in a limited way – is with regards to data. This is because the government of any nation has oodles of data – not that they can make sense of it themselves sometimes.

The idea of sharing it is also not without controversy. Do you want ABC AI Company to have access to NHS patient data? What can they see? Are they 100% sure it’s all anonymous – and are they sure it won’t ever come back to impact people as they try to get health insurance, or find a job? Given how time and again big tech companies have proven to be unreliable when it comes to being candid about how they use data – (Hello Facebook…!) – do we really want to go there?

This is what the UK Government says: ‘The AI Council and the Ada Lovelace Institute recently explored three legal mechanisms that could help facilitate responsible data stewardship – data trusts, data cooperatives and corporate and contractual mechanisms.

‘The ongoing ‘Data: A new direction’ consultation asks what role the government should have in enabling and engendering confidence in responsible data intermediary activity. The government is also exploring how privacy enhancing technologies can remove barriers to data sharing by more effectively managing the risks associated with sharing commercially sensitive and personal data.’

So, this is an example of where lawmakers can step in and make a difference, even if it gives this site something of a cold shiver to think of State-collected data being shared with companies that would sell their grandmothers for a fast buck. And when it comes to things like facial recognition – wow, that really is scary stuff.

Of course, there are benign use cases, as well as nasty stuff like surveillance. Medical use cases do have merit, and machine learning systems to help spot cancer do need plenty of training data. Using road use data to better model how traffic lights can be optimised also makes sense. But, the key thing as ever is always: are they keeping personal information out of the equation? Is this use case really benign? Maybe AI companies that use public data need to sign some kind of Hippocratic oath?

And of course, there is the great work of LawtechUK (which is also taxpayer-funded) in helping legal tech companies to get their hands on useful data, e.g. case law from the Ministry of Justice and other sources. Or at least that is the hope.

Conclusion

There is a lot in the paper, and much of it is word salad, but it’s commendable that the UK Government is supporting tech development. The main challenge for this site is that ‘AI’ is not one thing. Data is not one type of information. And tech talent will go wherever the money is and the most exciting projects are – and that is down to private business and individuals having great ideas about how to create value and make the world a better place.

Of course, the UK could announce a kind of Moon Shot style initiative, where it would bring the world’s best AI experts together and fund something immense all the way through that would totally change the world. But, what would that project be? (Answers on a postcard please to AL HQ).

Ultimately, although governments can tweak the law, e.g. about data sharing – with all the risks that entails, and can push some more money into grants for universities and other academic projects, what a government can do for ‘AI’ is limited. In part because, as said, AI is not ‘a thing’ – it’s a whole host of very different things that are highly sector and use case specific, and connected to a massive range of other technologies. I.e. AI is now better seen as a core component of the wider tech world, rather than a separate thing that needs its own special rules and regulations.

It’s hard to fault the intentions here, but the question is really how do we incentivise private business to increase tech development? And the short answer is: we should let the market figure that out. Companies that come up with good ideas that help people will prosper, those that flounder around, perhaps kept on life support by taxpayer money, will not.

In short, we don’t need a national AI strategy, and any changes to the law to allow the likes of Facebook or Palantir to get their hands on even more information about us in the name of ‘international competitiveness’ need to be made with extreme care. Meanwhile, much of the data that can be safely shared, e.g. case law from the courts, can already be shared under current rules, we just need those in charge of those departments to make it easier to do so – and that doesn’t need a national strategy or a change in the law.