‘Getting Medieval With Smart Contracts’ – Clyde Code

By Lee Bacon, Partner, Clyde & Co and founding member of Clyde Code, the law firm’s specialist smart contract unit.

Six months after establishing Clyde Code (the smart contract consulting unit of Clyde & Co), the prevailing hype and counter-hype scepticism has prompted us to reflect on where the market is now in terms of the successful adoption of blockchain, DLT and crypto technology in transactions.

We have been fortunate to be involved in some innovative and fascinating product developments in the DLT and blockchain related space. And, 2018 has seen an explosion of interest prompted, in part, by the Bitcoin fever over last Christmas and New Year. But, our core reflection is that if your product or project is not simplifying how you transact, something is wrong.

Reduced complexity is good. Less law is good. A central role for lawyers or contracts probably is not, is our conclusion.

Let’s take an example of what we mean by that.

Getting Medieval

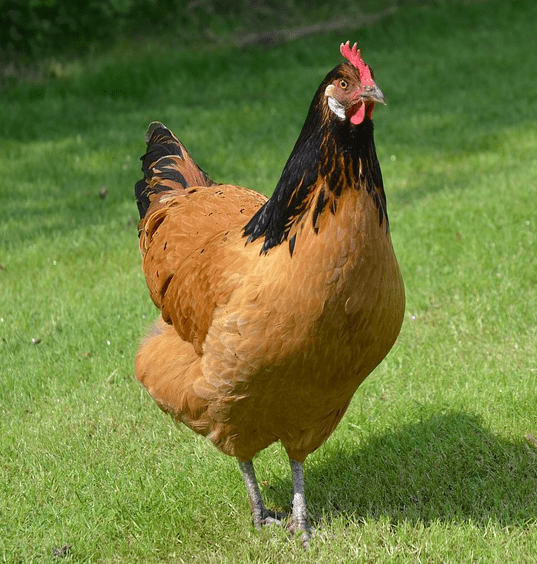

A medieval peasant, let’s say Godwin, who bartered a half-bushel of wheat in exchange for a chicken with a neighbour (let’s say Matilda) would (we assume) have done so knowing that the transaction was straightforward. He would not have thought to, or needed to, incur the frictional cost of preparing a document recording that agreement. Godwin knows Matilda and takes the risk in the barter because of an element of trust and simplicity.

In light of economic development, complicated trading structures and arrangements have arisen in order to allow parties to transact where the level of familiarity and trust that existed between Matilda and Godwin is absent. The new digital technologies – where suitable – can cut through some of that complexity.

In short your innovation should make you feel at least a little like a medieval peasant, leading a simplified life.

In 2017 interest in the blockchain sector firmly moved from the start up and digital worlds into the innovation units of established corporate industries. In 2018 interest has progressed into the business divisions of these entities as companies scramble to keep pace with competitors or to gain an advantage.

Beyond the Hype

However, the hype surrounding blockchain, crypto and DLT is now such that it is perhaps inhibiting realistic development. Often it is proposed for schemes for which it adds no value, or which have no credible commercial purpose. Conversely, its over hyped nature leads to scepticism as to its value at all, leading to it being dismissed as nonsense. Both reactions, we submit, misunderstand the technologies – still in their infancy in many cases – and the potential use cases.

Once understood, the potential for transformative change in the way in which business can be undertaken is significant; but it also becomes clear that blockchain and smart contracts do not have blanket application.

The successful projects start with the issue to be addressed – the matter of transacting – and then seek to open-mindedly consider how the new technologies can strip out layers in the value chain. This approach adopts a forensic focus on the underlying rationale of the transaction and questions incumbent execution methods. A cool head and steady hand are required.

New Opportunities

Conversely, the technology is often dismissed because it does not fit within existing structures, rather than because it cannot create value. The value proposition for new entrants and start-ups is that they are able to think afresh without being encumbered by dogma.

For example, sophisticated commercial insurers who query how the technology for automating contractual changes can be applied in a co-Insurance market; but who do not take the next step of querying how the efficiencies created can change the nature of a risk and displace the need for co-insurance if, for example, sufficient reinsurance capital can be deployed directly.

Or in the trade and commodities world, those who rightly identify that bills of lading cannot be transferred other than by the paper copy, without considering how contractual arrangements can be overlaid to bypass the current state of the law.

Our final reflection is to highlight the risk that the sector will be over-lawyered; and, yes, we recognise the irony. The proliferation of debate as to Smart Contracts and their enforceability and desirability often misses the fundamental point that parties do not want to enter into a contract but want to transact.

If a digital or codified basis for that transaction can be established with sufficient certainty then much legal dogma about contracts falls away. For example, when code incorporates the basis of the transaction then it is in our view unhelpful to talk about the code enforcing the agreement or resolving any dispute.

Rather the code – if put in place properly – simply transacts the agreement. We should stop seeking to squeeze the new technology into existing frameworks. Squeeze too hard and the pips will fall out.

Whilst certainly important that they are addressed, the core legal considerations remain on the periphery. We see these core considerations as:

- Clarity as to the agreement.

- Responsibility for the code – writing and maintenance.

- Clarity as to any input data (quality, accuracy and reliability).

- Understanding of the outputs – for example are they to be fully automated, or with an in-built pause or review mechanism.

- Agreement as to applicable law and jurisdiction in the event of a dispute or change in circumstance.

- Compliance with the regulatory framework in particular data protection, KYC and sanctions.

Each of these considerations sit alongside the core code.

So when working on transactions utilising Smart Contracts or similar, channel your inner medieval peasant!