It’s the Easter holidays, so here’s a repost of one of the most popular long reads published in the last 12 months. It was first published to explore the meaning of the EY acquisition of Riverview in August 2018. Since then EY has also acquired the LMS group of Thomson Reuters. The main part of this article is about the economics behind this, and similar moves by other participants in the legal market, and makes this article even more relevant today than it was last year.

—

As pretty much the entire planet has now noted, Big Four firm EY has acquired the UK-based LPO/ALSP Riverview Law, giving it a significant boost in terms of its ability to offer a far stronger managed legal services capability to corporate clients.

It’s well-known that the legal arms of the Big Four are expanding and they make it very clear they do indeed want to eat some of the traditional law firms’ lunch. But, the market was not expecting such a bold move as to take over one of the better known process-focused legal services businesses.

So, that is what has happened in a nutshell, but what does it all mean? Where does this all fit in terms of the bigger picture of market change?

Primary Legal Services

We could get into the nitty gritty of how much money Riverview will make for EY, or try and guess how quickly it will expand with EY funding its growth, but let’s not do that. The truth is whatever Riverview was before will change now under EY’s ownership and we cannot say yet how the clients will respond, or how much work over the next few years will find its way there.

Though, a good guess would be to say Riverview will be very, very busy, given EY Law’s global footprint and the wider EY’s huge client base that includes many of the leading companies on the planet, each with significant doc review and analysis needs.

Instead, let’s consider how this deal fits into the bigger picture of legal market change.

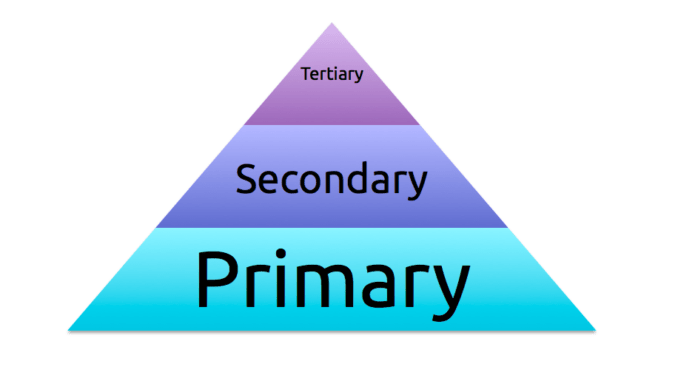

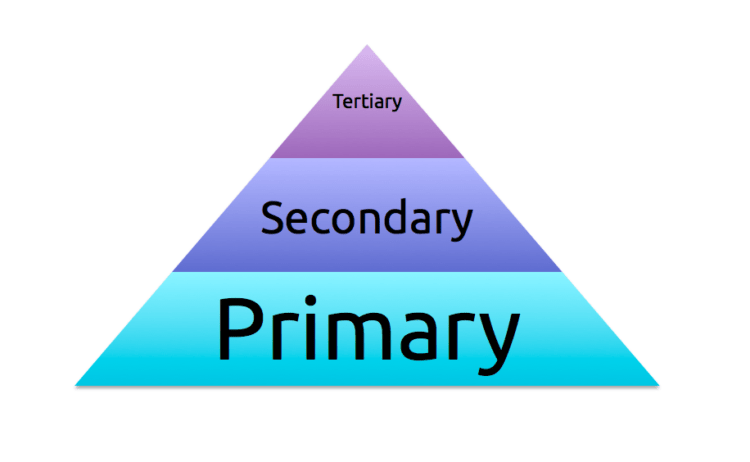

What all LPOs, ALSPs, managed legal services arms, process units, Northshored bases, outsourced bases and whatever other euphemism you want to use all do is the same: primary legal labour (PLL).

What is primary legal labour? Consider the table below:

Primary legal labour (PLL) – lower value process work, such as document review, simple form filling, and ‘bureaucratic’ activity. (The work of paralegals and junior associates).

Secondary legal labour – more value-added work, such as putting together relatively standard contracts, overseeing some of the primary work, assembling materials for more experienced legal staff to make judgments upon. (The work of mid-level to senior associates).

Tertiary legal labour – this is the most high value work, it requires expert and experienced insight, high grade project management skills, it relies on judgment, and it is often about very close working relationships with the client, i.e. it’s very much about human skills too. (Classically the work of equity partners, though how many partners also slip into doing too much secondary labour varies from business to business. And inside a corporate this would be the work of GCs and senior inhouse counsel.)

The global economy and society as a whole needs all of this, just as we need primary, secondary and tertiary industries, from mining and agriculture, to sales, to management consulting. The bigger issue is: how should we divide up these levels of production to be the most effective and beneficial for society?

The EY/Riverview Law deal is clearly part of the primary legal labour section of this system. Traditionally, law firms have been offering a combination of all three levels of legal labour – which is one reason they are so pyramidal in structure.

If you strip out the bottom two levels you end up with what looks like a high-powered English barristers chambers, where everyone is expected to carry their own weight and you’re expected to be able to handle significant client matters very early on.

Looking at this the other way, what happens if we just cut off the bottom level and separate out the process, or primary legal labour (PLL) section? Well….then you have an LPO, an ALSP, a managed legal services arm and so on.

But why would you do that? Here are some reasons:

- A separate business unit can more easily focus on standardised work patterns.

- It can be moved away from the secondary and tertiary parts of the business to relocate it to a cheaper site, which can also mean cheaper legal labour (which is usually sufficient for this process work).

- Once separated from the rest of the pyramid there is less pressure to behave like a pyramidal organisation, i.e. no more ‘up or out’, in which case staff can look to a long career focused on perfecting this process work, rather than seeking to become an equity partner one day.

Why would clients want this? Here are some reasons:

- Cost – PLL units will generally be cheaper than those primary labour parts of law firms that do this work in integrated, HQ-based groups (due to property and labour cost savings).

- Capacity – a PLL unit is a volume play and therefore will be set up to cope with whatever a large client throws at them. This is more convenient than asking a law firm to assemble a big team of paralegals who have never worked together before for a one-off job.

- Reliability – PLL units do one thing: process work. They’re good at it, they know how to manage this work and do it quickly, no need to reinvent the wheel again and again.

This is where the EY/Riverview deal fits in. And in that respect it’s not breaking from the patterns already well-developed in the legal market. What is important is that EY, and many others, including rivals such as PwC, have really grasped just what a massive opportunity this is.

I.e. if we accept all of the above, then the idea that large corporates should be handling process level legal matters in any other way seems bizarre. Why pay more for a worse service provided by ad hoc primary legal labour, why not use a dedicated PLL service?

And then of course, we get to the big enchilada: automation and the use of AI systems.

AI, Automation and What’s Next?

AI and automated document review systems still need people as part of the process. But they can create additional efficiencies in already very efficient PLL units. Therefore any business, law firm, LPO, Big Four firm, or anything else, would be nuts to not exploit AI as well. And many do. From Thomson Reuters using eBrevia in its managed legal services arm, to ALSP Elevate using Kira Systems, to Slaughter and May using Luminance, to PwC making use of Seal Software.

The future now revolves around three key questions:

- Will clients now take a far more industrial and pragmatic approach to PLL? Will they become far more ready to separate out all PLL that is of sufficient volume to be done by the best provider, wherever they are?

- Will the businesses providing PLL services really exploit AI and automation to the max? And if they do, will this then create a fierce battle for market share? (Because the more you automate the more volume you can take, i.e. the more market share of available PLL work you can own.)

- Will some law firms decide to drop PLL work and if they do what will that do to their business model? (My guess is that they will hold onto it for dear life, but it would be amazingly brave for a firm to say: OK, forget about this PLL work, now we just do higher value work. That would create total mayhem with its recruitment and training model too. In which case, let’s not hold our breath on that one. But, who knows, maybe someone will try it? I suppose you could say some of the ‘lawyers on demand’ services that provide partner level ‘temps’ are almost like that, although they are not true firms, as such.)

Conclusion

The EY/Riverlaw deal matters, but it matters most because it is part of a far larger picture: the incremental industrialisation of the provision of legal services to the global economy and society as a whole.

It makes little sense to do high volumes of process work in a continually ad hoc and expensive manner, recreating the wheel each time and making the client pay for this inefficiency.

It also makes no sense today to run a ‘bodyshop’ only system when there is tech that can greatly reduce the time needed to do that process work.

And, for the owners of these PLL units, whether EY or anyone else, once you see a PLL group truly as an industrial unit, which is owned by whoever…maybe partners, maybe owned by someone else….then there is everything to play for in terms of gaining more market share and automating more (so that you can increase volume while keeping costs generally the same), as the profit runs to you.

Are we about to see a radical revolution in the legal market? Not yet. But we are getting there. LPOs for all their usefulness have still only a small part of the market. Many clients still shop for legal goods the traditional way. But, that is changing, slowly – and the EY deal is a sign of things to come.

By Richard Tromans, Founder, Artificial Lawyer + Tromans Consulting

[This is an Easter holidays repost. Normal publication will resume on Tuesday 23rd April.]