The California State Bar’s Task Force on Access Through Innovation of Legal Services (ATILS), is looking at the dangers of ‘dark pattern’ marketing that could arise from tech companies providing legal services to consumers.

ATILS is also looking at the potential for putting in place a regulatory sandbox that would act as an intermediate stage for more novel business models providing legal services in California (see more below).

The ATILS project is seeking to develop new rules by which California could open up its legal sector and allow a more diverse range of entities to provide legal services.

In a recommendation paper to the Task Force, Dan Rubins (of AI company Legal Robot) who was the main author, Mark Tuft, and Kevin Mohr, set out concerns around what they term as ‘Legal Service Technology Providers’ or LSTPs – i.e. tech companies that are offering legal services – that may make use of ‘dark pattern’ marketing that could manipulate consumers into making bad decisions about what they want or need to do in relation to a legal problem.

In an interview with Artificial Lawyer, Rubins said: ‘We really listened to public comments [following the opening up of the Task Force’s work to comment from the community] and drafted this recommendation to address those concerns.’

Classic examples of dark patterns in an online sales platform would be scenarios where the system pushes you to make decisions too quickly to make a reasoned consideration of other options (e.g. as seen in hotel and flight booking sites), or where a user may be coerced into buying additional products and services (e.g. financial services companies pushing you to buy additional insurance that may not really be needed).

It appears that the view from this Task Force team is that if retail companies and financial services have ended up this way, then there is a real risk that legal services could go the same way – and that needs to be nipped in the bud, depending of course on what level of de-regulation the ATILS project is able to attain in California for non-traditional providers.

That said, they also note that even today’s law firms might need to face a ban on the use of such practices.

The team states: ‘In California, many dark patterns from previous eras are already banned….That so many consumer protection laws have been required illustrates the tech industry’s creativity in developing dark patterns to increase profitability.

‘LSTPs engaging in authorized practice of law activities must avoid employing dark patterns in their products (perhaps a ban on such behavior should include lawyers as well). To aid technology providers, the regulator should publish, partner to distribute, or otherwise encourage education on dark patterns.’

The recommendation paper also states, among other things, that: ‘LSTPs must make reasonable efforts to mitigate or eliminate bias and other potential negative effects when deploying algorithmic systems.’

As explored by Artificial Lawyer before, the realm of bias is a can of worms – albeit a fascinating anthropological one. This is because all people are biased in a myriad of ways, it’s just that what we label as ‘bias’ are in fact decision systems, or beliefs, that we find morally reprehensible in the present day, while the biases that we see as ‘good’ or ‘acceptable’ are glossed over and ignored.

For example, a recruitment system could be biased toward post-graduate candidate only short lists – which today would perhaps not raise too many eyebrows, at least for a senior position in a company. That would be seen as suitable and ‘benign’ bias by many, or in fact, ‘not biased’ at all. That said, people who did not have post-graduate qualifications may feel this is an unfair bias. In short, it’s a battle over what we believe is socially acceptable – and that is always in flux, and often hotly debated.

How you end up with ‘morally acceptable bias’ in your algorithms is therefore an interesting question. And presumably they would need to be updated every few years, as what is seen as acceptable steadily evolves, as it does in all societies, (just watch a TV show from the 1970s, for example, to see how much things have changed in a relatively short time).

The recommendation concludes with a very serious note: ‘The regulatory entity of LSTPs should have the authority to reject, hold, or cancel an LSTP’s certification/license/approval to provide authorize practice of law products and services that violate any of the foregoing principles, subject to administrative appeal. LSTPs that continue to operate would no longer be eligible for the proposed safe harbor and would therefore be subject to existing rules and statutes regarding Unauthorized Practice of Law, including criminal prosecution.’

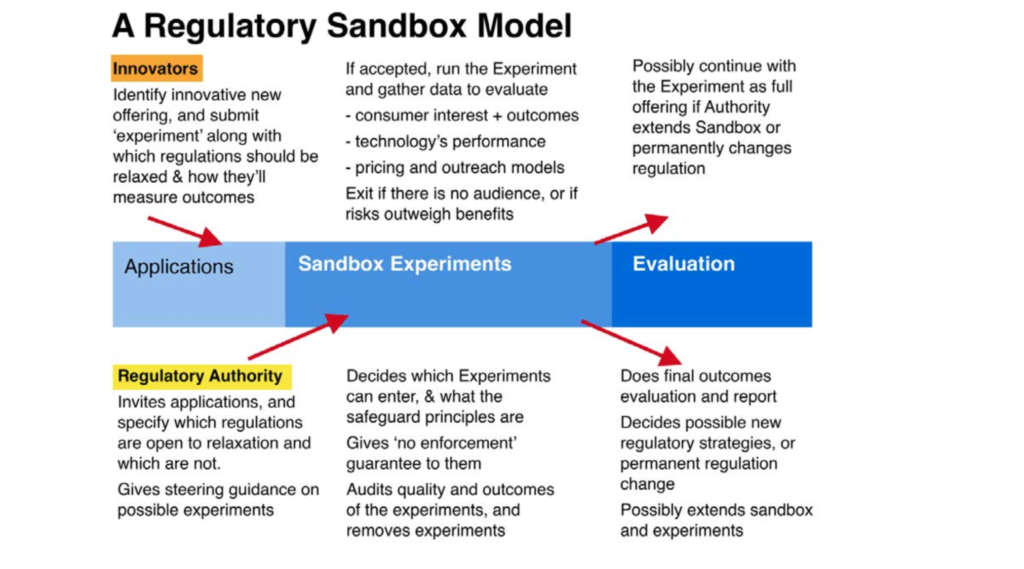

One other area of interest that Artificial Lawyer spotted among the topics now being explored was some new thoughts from the Task Force on potentially introducing a regulatory sandbox, which would operate as a ring-fenced enclosure for those entities with new legal business models that may not fit into the current system.

These ideas were in part inspired by work already carried out in Utah.

A recommendation paper by Joanna Mendoza, Bridget Gramme, and Andrew Arruda (from the legal research pioneer ROSS), sets out that such a sandbox would be there for:

‘…Any business model, service or product that cannot be offered under the current rules and statutes will be able to apply and be considered by the oversight body [to be part of the sandbox].

‘The oversight body will give priority and a reduced fee structure to non-profits as well as for-profit entities that propose providing services specifically designed to address areas of most need as identified by the 2019 California Justice Gap Study. Other entities/services may be considered by the oversight body as well, but the priority and fee structure preference shall be with the formerly mentioned entities/services.’

And that:

‘….A sandbox is not set up as a permanent regulatory structure. Critical to entities/services that would participate in a sandbox is that they be allowed to continue providing their services so long as it is performing as intended and not harming the public.

‘Therefore, a crucial condition of the sandbox model is that a structure is set up after the sandbox is concluded that will allow the services to continue under those conditions. No permanent regulatory structure or rule changes are proposed at this time as any such proposals will need to be informed by the sandbox experience and data derived therefrom.’

It’s an approach that many countries have used in other areas, such as for financial services. It allows regulators to become familiar with how a new approach to service delivery works without having to give ‘carte blanche’ authorisations. The ring-fenced nature of the system also means that regulators are not overwhelmed by a huge number of new entities.

After enough time passes, data is gathered and lessons are learnt, and then more permanent regulations can be put in place, if that is seen as desirable.

The scheme would be funded by fees charged to the participants, they added.

Below is a diagram of how the model proposed in Utah would look:

Overall then whatever comes out of the work of ATILS, its members are working through many of the toughest issues today associated with the legal sector. Maybe the end result won’t be the broad de-regulation hoped for by many (and equally feared by many lawyers as well…), but it seems highly likely much good will come from their work.