Stephen Metcalfe, a Conservative Member of Parliament, has asked whether the UK should install a dedicated ombudsman to deal with issues created by algorithmic decision-making, such as occur in some AI systems.

Metcalfe was speaking at the All Party Parliamentary Group on Artificial Intelligence (APPG AI) Evidence Meeting 2, which covered ethics, legal decision making and moral issues. The meeting was chaired by Lord Clement-Jones at the Houses of Parliament last night and Artificial Lawyer was kindly invited along.

Several speakers at the APPG AI event raised the issue of how we meet the challenge of AI systems making decisions, especially in areas such as justice, medicine or finance, that impact the individual.

Metcalfe asked: ‘Do we need some kind of ombudsman so you can challenge these decisions [made by algorithms and AI systems]? I think it’s too early to regulate [AI], but we do need a way to challenge decisions.’

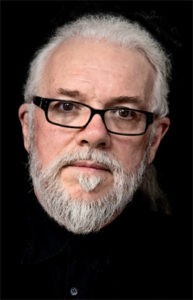

Metcalfe’s views may carry some weight given that he is also Chair of The Commons Science and Technology Select Committee.

How the ombudsman system would work was not set out, but presumably they would hear complaints against a decision made by either a State-operated or private company’s algorithm where an individual felt they had been discriminated against, or the decision needed explaining.

Other speakers also called for greater algorithmic transparency, although, panel guest, Noel Sharkey, who is Professor of AI and Robotics, Sheffield University and Co-Director of the Foundation for Responsible Robotics, stressed that the responsibility was on humans, rather than trying to blame machines when things went wrong.

He added that the AI industry needed new rules to govern its behaviour, though it was important to do this ‘without stifling innovation’. His argument was that we need to focus on the human programmers, not the code, i.e. it’s the decisions made by humans to cede power to algorithms that need to be looked at most carefully and how bias is then fed into those calculations.

‘Machines don’t make decisions, it’s the programmers,’ Sharkey said.

‘We need a chain of liability and responsibility,’ he added, while also pouring doubt on the EU Parliament’s idea of giving AI systems a legal personality.

That is to say, Sharkey sees the way to hold AI systems accountable is to hold their creators accountable, rather than trying to see AI decision-making algorithms as separate entities that were making choices and which could be blamed for anything that went wrong.

APPG AI Chair, Lord Clement-Jones, who is a lawyer by background, added that the idea of who or what is making the actual choice of outcome was very important when looking at liability. He raised the example that in criminal law there is usually a ‘mens rea‘ or conscious intention to do something if a defendant was to be found guilty, but noted that in the case of AI ‘where is the mens?’ [i.e. the mind].

The point about liability created a lively discussion, with one member of the audience from a tech company stating that if individual programmers were ever held liable for a mistake by an algorithm it would kill off the AI sector, as no one would ever want to work in such an exposed position. They also noted that nearly all computer programs had a tiny percentage of coding errors.

However, other speakers responded with the argument that the liability issue for AI was no different than that for automotive companies. For example, if a car company’s customer was killed due to a brake pad fault, no engineer would be prosecuted, rather the corporate entity would face a legal claim and this would be defended as any other claim of liability would. In which case, programmers should not be afraid. But, this did raise the issue of liability for AI companies as a corporate entities.

One of the guest speakers, Ben Taylor, CEO of expert systems maker, Rainbird, added: ‘We are looking at the issue of liability very carefully. We need a framework to reassure people.’

Taylor added that if one looked at financial services, that AI systems there would not be taken up by big institutions unless a clear legal framework existed. Rainbird also works in the legal sector and has worked with international law firm, Taylor Wessing, on creating a legal compliance-checking tool for them (which Artificial Lawyer covered recently).

‘The law has a long way to go to catch up with automated decisions,’ he concluded.

Overall, law makers seem to be faced with a complex balancing act of introducing some reassurance for the public that using AI and/or complex algorithms will provide fair and just outcomes, while also not introducing regulation that would stifle the sector even before it had started to become established.

It was also clear that the way discussions about AI proceed today, which for now are conducted by a relatively small group of experts and industry followers, would not last forever. One guest speaker, Marina Jirotka, Professor of Human Centred Computing, University of Oxford, said that there had to be a proper public consultation on the use of AI and that NGOs should be invited to give their views on forming any future regulation.

It is therefore unclear where the UK is heading at present in terms of law and AI, but it would seem likely that calls for some form of regulation, especially to clarify areas such as liability and to establish an ability to challenge algorithmic decisions via an ombudsman, will eventually lead to some type of new law in the medium to long term.

The guest speakers included:

- Kumar Jacob – CEO, Mindwave Ventures Limited

- Marina Jirotka – Professor of Human Centred Computing, University of Oxford

- Dave Raggett – W3C Lead, The Web of Things

- Noel Sharkey – Professor of AI and Robotics, Sheffield University, CoDirector Foundation for Responsible Robotics, Chair ICRAC, Public engagement

- Ben Taylor – CEO, Rainbird Technologies

1 Trackback / Pingback

Comments are closed.