Efficiency is at the heart of legal technology, i.e. less time or effort expended to get the desired result. Yet, efficiency is also why people pay for $1,000 an hour lawyers. This is because efficiency is all about getting what you want. Let me explain.

Easy Wins

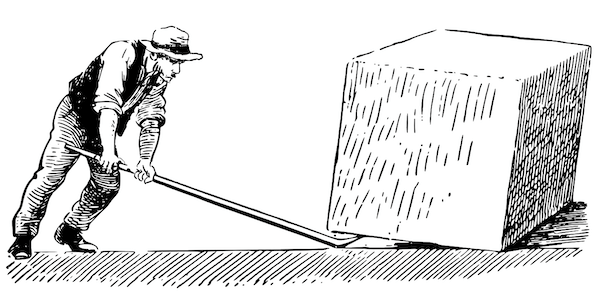

When one considers the word ‘efficiency’ there is a tendency to think in purely mechanical terms, e.g. less energy and effort put in to get the result out, such as using a lever to lift a lump of rock (see image above) – which is way more efficient that using a large group of people who are just using their hands.

It’s also often seen in relation to economics, e.g. it’s way more efficient to buy cleaning products in bulk as you can get special deals on a dozen dishcloths.

And we see this clearly in the legal world as well.

For example, it’s way more efficient in terms of effort and cost to create a self-serve portal in a large company to help employees download and complete a basic NDA. There is an initial investment in terms of legal labour, i.e. subject matter expertise and risk analysis; there is process mapping and outcome analysis; and some technical input to digitise this and make it available to people on their desktops. There may also be additional expenditure, e.g. fees for the use of doc automation and/or no-code workflow software.

But, once the initial effort and costs have been sunk into the project it should then start to deliver. Documents that really don’t need legal attention every time they are created can now be handled with the minimum of fuss. This provides multiple efficiency-related benefits:

- The need is met more quickly, which is good for the company as they are not wasting the time of the employees, or slowing down their work.

- It allows the inhouse legal team to focus on higher value matters – which is why the company hired them in the first place.

- They will ultimately save money over the long-term, as employing commercial lawyers to hand out basic NDAs is an additional expense to the operating costs of the business.

It could also help to reduce risk because a standardised document which has been created by the legal team – and is regularly updated – will make sure that employees 1) get the right legal agreement for their needs that meet the company’s risk profile, and 2) it’s such an easy process that employees never skip this step, or try and bodge it with an old document they’ve found on Google. Less risk means less chance of damaging claims and losses of IP.

But, with this last one, is the thing about risk really connected to efficiency? Yes, because efficiency is about much more than just time and money.

Complex Needs

It’s tempting to see efficiency as only a mechanical thing, that it’s only about the material inputs and outputs in the process. But it is way more than that. Efficiency plays a part in nearly all aspects of our lives, and the same goes for legal work.

To understand that we have to appreciate that what we are ultimately talking about is ‘desire’, i.e. a person wants to satisfy a need. And these needs are sometimes quite complex and at first glance don’t appear to have much to do with the mechanics of processes….but they do.

Let’s take the example of a large, multinational company that is buying another business in an M&A transaction. The owners of company A want the deal done quickly, for sure, but they also want it done right. There is a lot of risk involved here. There is due diligence to be done, there are regulatory frameworks to be navigated, there are the employees of company B to consider (as not all will be joining), then there is the debt issue (as company A has borrowed a load of cash to make this deal), and then there are the IP, tax, and real estate issues involved. And of course, aside from all of that they need lawyers who can handle the deal, work well with the banks, regulators, the other lawyers for other parties involved, and are certain to be confident in their legal advice across multiple jurisdictions.

And the list goes on.

Now, efficiency is occurring here at different levels. At the highest level it is (in most cases) more efficient for the GC of the company to bring in a global law firm, or group of top tier firms that are known to work well together. The first question is probably not going to be about cost or time.

The first question will in fact probably not even be said out loud, as it will be a question the GC asks themselves, which will be something along the lines of: ‘In this massive, company-shaping deal, which has billions of dollars involved, and many people’s reputations wrapped up in it (including my own), which law firm(s) shall I choose to help me?’

Understandably they will pick a firm they know well already that can help. Why? Because this is efficiency at work. Picking someone you know already to do something you know they can do is a form of efficiency.

Picking a firm with a very solid brand in the market for handling complex matters is also a sign of efficiency, as it shortcuts the need to do a complex analysis of the whole legal market to find the service provider you need.

And given that the deal is massive, the top line legal cost is also not going to be a big issue. In fact, not worrying about the cost could be seen as an efficiency play. I.e. if you haggle over the costs and refuse to take advice from the top firms you are creating a new, long and slow process of finding a new advisor, who may charge less, but to ensure you keep risks down you’ll have to do a lot more due diligence in picking such a new, cheaper firm. This is time-consuming for you, just as the company wants to get the deal moving.

But…..what about process, and legal tech, and innovation, and all the things that Artificial Lawyer is always talking about?

They are still there, but they are embedded inside the delivery of the deal.

If you follow the ‘hierarchy of desires’, then the speed and cost elements are subordinate to the higher need of getting the deal done correctly and with the risks reduced.

Now we get into the breakdown of the parts of the deal. The high-level negotiations – which the lawyers are only one aspect of, as it’s the business’s C-suite who are fighting for what they want – are not really fee sensitive.

But the due diligence? For sure. The experienced GC knows there is no need to do a 100% manual review, so let’s drive efficiency on this specific economic area. It may also be faster to bring in some tech.

And the production of the new employee contracts, of which 1,000 of the 2,000 documents are basically the same but with different names on them? How about we go down the doc automation route? Of course that makes sense.

Efficiency is Very Human

The key point here is that efficiency isn’t that simple. It’s also far from just being mechanical in nature, it’s actually very human. In fact, one could say that efficiency is one of humanity’s guiding principles and is a foundational driver for civilisation.

The challenge is squaring the complex with the simple – and it’s also here where you find many people at loggerheads, even though they are actually arguing (or agreeing in fact) over the same thing.

I.e. someone might say to me: ‘Look, choosing this top global firm to do this deal has nothing to do with efficiency. We chose them as they have a track record in this kind of deal. To start with a blank piece of paper would be slow and may even increase risks that harm the company.’

Meanwhile, another person says: ‘The reason why we chose this ALSP to do the process-based review work for the deal is all about efficiency. The client wanted to save time and money, so we worked with an ALSP as they had the workflow expertise, the right staff, and the right tech tools, to enable this.’

But, they are both examples of efficiency, just operating at different tiers of experience.

The real question is therefore: where is the dividing line between the various efficiency decisions? The short answer is that it blurs and has much to do with the sophistication and experience of the buyer. But there is no exact boundary, although there are polar ends to the equation.

I.e. choosing the top firm is an efficient action as it prevents the need for a long, complex, and probably unnecessary search for advisers for a matter where penny-pinching on the top-level advice is a false economy. Going on brand, reputation, personal relationships and other very human signifiers is a perfect example of efficiency.

But, likewise, (and it may seem paradoxical), demanding that the more process aspects of the job are done with mechanical efficiency also makes sense.

Somewhere in the middle is a cross-over point, where economic, and time, and effort, considerations become subordinate to the greater desire. But all of them are about efficiency, just on a different scale.

The point is that human beings are complex. We can see the common sense in paying top dollar for high-risk work (as it reduces the need to haggle and search around, and it quickly gives us confidence and security, i.e. it’s very efficient in meeting our needs), and in the very same deal we may squeeze the supplier for economic savings on the parts of the deal we view as lower risk work.

We do the same thing in our own lives. Take a look around your home. A dishcloth has only ‘mechanical value’, i.e. it’s a basic tool that does a basic job. Now you could buy a dishcloth with golden threads, but even a billionaire would recognise that this was a waste. It would not be efficient – and it would not meet any meaningful desire.

Likewise there may be things you buy that achieve the results you want, but the economic and efficiency aspects are lower down the hierarchy, so they get overruled. E.g. at a shop you buy a luxury object that brings you tremendous satisfaction, and in fact a kind of satisfaction that would take far more time and effort to achieve if you didn’t buy that thing. I.e. meeting the need through buying the luxury object is an act of efficiency.

Conclusion

Although efficiency is indeed all about getting to the satisfaction of your needs as easily as one can, it’s not always all about the mechanical process, or all about utility. Efficiency is fundamentally about getting what we want, and that takes many forms.

By Richard Tromans, Founder, Artificial Lawyer, May 2022