By Christopher Karageorgis.

‘The single biggest problem in communication is the illusion that it has taken place.’

― George Bernard Shaw

If a lawyer were to tell you that you have a ‘likely’ chance of being successful in a dispute, what probability would you assign to that statement?

Or consider this: if you were told that between gaining £500,000 and losing £100,000 you were ‘more likely to win than lose’, would you take that risk? If not, would you settle for a lower amount? If so, for how much?

The problem with using words to evaluate legal disputes is that lawyers often use vague terms such as ‘probable’, ‘likely’ or (of particular relevance to the English legal system) the ubiquitous ‘reasonable’ to express their opinion on the likelihood of success. Consequently, the decision-makers, whether clients, investment committees or board members, are left with the unenviable task of interpreting these ambiguous assessments. This invariably leads to miscommunication and poorer decision-making.

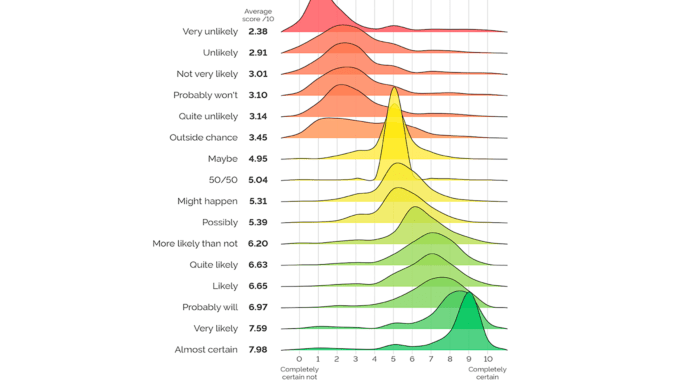

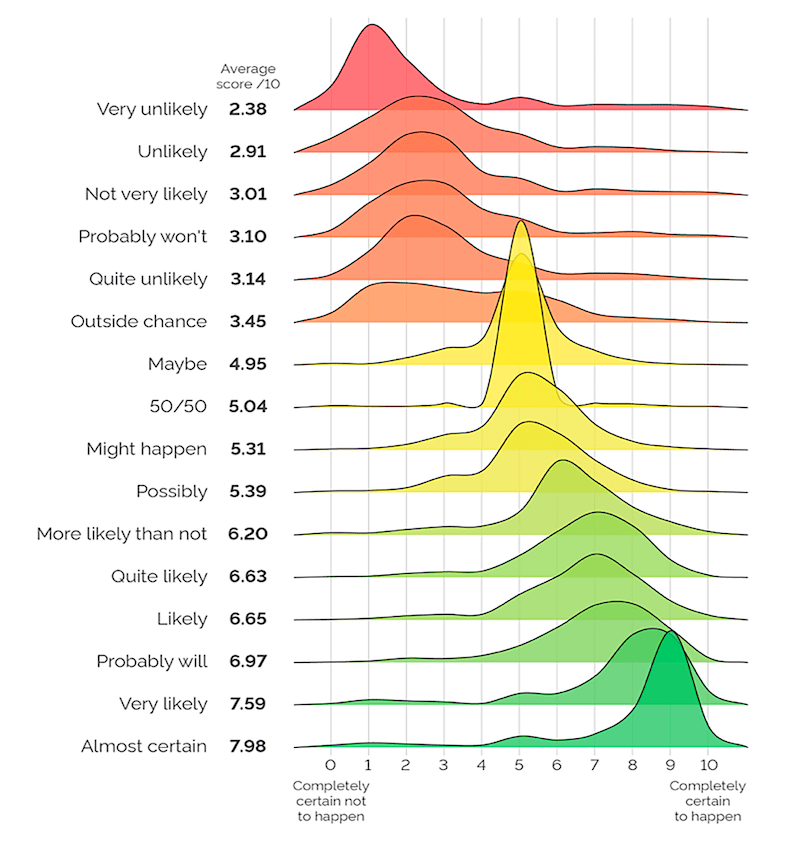

To support this, a 2020 study conducted by the UK government (see Fig. 1) asked thousands of respondents from all over the country to describe on a scale between 1 to 10 how likely something was to happen using various words or phrases. Taking the word ‘likely’ as an example, while results showed that on average it was thought to be around 6.65/10 in terms of likelihood, some people believed it to be a 4/10 chance of something happening and others a 9/10 chance.

Similarly, in trials conducted with lawyers who were asked to assign a percentage probability range to the phrase ‘it is very likely we will win’, some assigned a 60-75% chance while others believed it was an 85-100% chance. What’s even more worrying is that on several occasions these wildly different views were expressed by two partners from the same law firm who often worked together on the same cases.

The results show that qualitative evaluations can be very misleading as their meaning is subjective – that is, based on the thoughts and feelings we ascribe to them at any given time.

So, what’s the solution?

Quantitative analysis allows us to accurately measure the likelihood an event will occur by taking the non-systematic method of using words and replacing it with a numerical system that we are all familiar with. It offers little scope for misinterpretation. By doing so, legal professionals are better positioned to create a better understanding of the key issues in a dispute and clients are better positioned to assess the advice and decide on the next steps.

…but isn’t this riskier?

We lawyers are risk averse by our very nature, and we can all appreciate that there is little room for error in a career that is dependent on the accuracy of your advice. However, as highlighted above, by using words there is already a risk of miscommunicating with your client, which can lead to the failure of one of the key legal soft skills: managing your client’s expectations. This in turn can lead to incorrect decisions being made and risks destroying the most precious thing of all to a lawyer: their relationship with a client.

Contrary to it being riskier, for quantitative analysis to work well, it requires a much deeper analysis of the facts of the matter in order to ascribe a percentage or decimal value to the probability of success. In a nutshell, explicit, detailed explanations of probabilities and risks will lead to a better analysis.

What’s more, legal professionals are already expressing a percentage range (albeit a subjective one) when using words to evaluate disputes. When describing the chances of success in litigation, a lawyer will have their own opinion as to what percentage range this would equate to when queried.

So, by using numbers instead of words all the legal professional is doing is quantifying the word they would usually use to describe the chances of success in any given instance. Of course, the usual caveat to clients applies – setting out the ‘known unknowns’ in any assessment and advising that this is liable to change as the dispute progresses.

‘The goal shouldn’t be to make the perfect decision every time, but to make less bad decisions than everyone else.’ – Spencer Fraseur, ‘The Irrational Mind: How To Fight Back Against The Hidden Forces That Affect Our Decision Making’.

Ultimately, being a lawyer is more than just advising clients. A lawyer needs to understand risk, probability, and the full range of potential outcomes to effectively advise a client.

We at Eperoto solve all these problems with our online tool which encourages legal professionals to use quantitative decision theory to model their disputes via what we like to call a ‘legal tree’. The legal tree is constructed branch by branch, with lawyers setting out the legal questions that are likely to be tried in any given contentious matter. Evidence is analysed in the usual way and all possible outcomes are required to be considered.

However, instead of gauging the likelihood of any legal question succeeding, a percentage probability is entered at the end of every branch (or ‘node’). The careful consideration of the likelihood of each possible outcome results in a deeper understanding of the case. The numerical output (known as the ‘weighted value’) at the end of each branch, provides a far more accurate reflection of the chances of a result going a particular way. The weighted values can then be combined to produce an estimated monetary value (or ‘EMV’) which, after factoring in other uncertainties such as the probable costs award, interest, insurance, and bankruptcy/enforcement issues, more accurately reflects the value of the claim.

As I have hopefully highlighted above, using words to evaluate legal disputes can lead to misunderstandings between parties with dire consequences. When someone says ‘likely’, one might understand a 55% chance, another a 75% chance. Extrapolated across multiple complex analyses in a single claim, this will invariably lead to poorer decisions being made on how best to proceed with matters.

Quantitative decision-making is already being practised in industries where accurate decision-making is absolutely critical: public health services, investment banks and government bureaus such as the CIA, for example. Though some lawyers around the world already perform similar analyses (albeit carrying them out in a more cumbersome, time-consuming method via manual calculations in spreadsheets), there is no reason why quantitative analysis should not become the default metric in an industry where good decision-making is also absolutely crucial.

A lawyer myself, I would argue that the law and the language surrounding it is so complex that it already requires a professional to interpret it. So, let’s dispense with any further need to interpret what is already an interpretation.

It’s time for the law to shift from the poetic to the scientific.

…that being said, when reviewing this article, my partner advised that it was ‘okay’, and I asked no further questions – a rare instance where you might prefer a qualitative analysis and to make of it what you will. A solid 8/10 it is then!

[This was an educational think piece for Artificial Lawyer by Christopher Karageorgis, Director, Eperoto.]