Yesterday (Monday 12) saw the beginning of The International Conference on AI and Law (ICAIL) and a specially convened workshop with the intention of building bridges between the world of legal AI academia and the lawyers and associated stakeholders who are using, or will use, this new technology.

Bringing together groups of people who don’t naturally move in the same circles, i.e. those who work in commercial law firms and very specialised AI academics, is never going to be easy, but the ICAIL workshop at King’s College, London, was a valiant and largely successful beginning to this endeavour.

The ICAIL event will continue over the rest of this week, but Monday’s event was special as it was designed for the lay person. In the audience were lawyers, legal engineers, CTOs, heads of innovation, law school academics, other legal AI academics who had popped in out of interest and also some legal tech media. This is what went down, with an exploration of the challenges and opportunities ahead at the end.

–

After some organisational bottlenecks that reminded all the commercial law people that they weren’t in Kansas any longer, the workshop began. Pinsent Masons legal engineer, David Halliwell, kicked things off with a succinct and clear overview of how his UK-based law firm saw the world of AI and automation.

Probably the key takeaway was Halliwell’s focus on the practical uses of technology and making better use of data. He noted that the firm now had 12 ‘knowledge engineers’ who were not just playing with legal AI tech, but getting to grips with legal process management and leveraging data to create value for the firm and the client.

For Halliwell, legal engineering demanded plenty of people to give human insight into the legal data collected and extracted. ‘Tech cannot do it all for you,’ he stated.

One point that stood out was his description of how after client data had been collected up and analysed by AI systems, this new and refined database became ‘an asset of value’ for the client. I.e. using AI turned an amorphous mass of unstructured data into something of real use to the client that they could keep going back to.

He also stressed that we were nowhere near general AI and that no system on the market at present was smarter than a cockroach. Halliwell also pointed out jokingly that Pinsent Masons had not yet hired any cockroaches either.

Halliwell’s final point also resonated. He returned to the popular meme that AI will end the existence of lawyers, but turned it around by concluding: ‘If you don’t allow tech in [to your firm] then it’s going to impact your existence.’

There then followed two short talks by two AI experts from the Department of Informatics, King’s College London, Isabel Sassoon on Machine Learning and Qi Hao on natural language processing (NLP).

These were competent and helpful overviews of some of the key ideas and methods associated with machine learning and NLP, which together form the tech backbone of the majority of legal AI applications, given the law’s dependency on unstructured textual data.

To some degree what these did was highlight the barriers lawyers and those in the legal sector have in coming to grips with AI technologies. While Hao and Sassoon did a good job explaining the basics, they had to use a lot of terms that people not in the AI space probably had not heard before. While the tech vendors and legal engineers felt comfortable considering the differences between supervised machine learning and unsupervised learning using a neural network, it was not clear how much the rest of the audience understood.

Later, as one or two lawyers from smaller firms noted in the Q&A at the end of the day, some firms are still struggling with the most early stages of document automation. While the academics did the best they could, this only heightened the sense of the gap between those who have engaged with technology and those that haven’t yet.

But, we have to start somewhere. Perhaps Sassoon and Hao’s talks will have inspired some lawyers to want to learn some more, and perhaps that is the best that can happen for now.

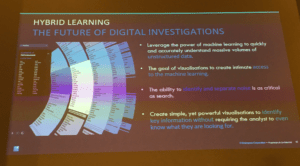

Then it was onto Brainspace, which showed off some of their data sorting tech, which helps lawyers to cluster, tag and classify large quantities of legal data, with what appeared to be a strong focus on key words. However, the graphical representations of the extracted and sorted data were impressive. The company stressed that great visuals send a more powerful message that helps to drive engagement of lawyers with the data. I.e. if it looks interesting and enticing graphically, lawyers will take the time to explore the data, whereas if it was all just piled into an Excel sheet, they’d probably lose interest.

That may not sound like a very profound point, but when we are in a period when most lawyers feel uncomfortable around more complex legal tech, then any UI/UX improvements that can break the barrier between lawyer and NLP/ML applications could prove to be very important.

Next up was Rick Seabrook, European Managing Director of US-based expert systems company, Neota Logic. Seabrook got into the details of how Neota worked, giving several examples of probabilistic inference that went far beyond simplistic logic trees that earlier expert systems had used.

For legal AI fans, the one aspect that stood out was Seabrook’s mention of how they are working with Kira on combining their applications to create a much more powerful stack of technologies.

This has manifested itself via Kira conducting the document analysis via its well-developed NLP and machine learning capability, with the results then linked to Neota’s ability to provide a sorting and perhaps most importantly an ‘interrogative’ layer on top. Or, put another way, Kira provides the key information from the unstructured mass of data, then Neota helps the lawyers do something more using its Q&A system, such as making decisions about certain documents or legal issues, such as their risk level, based on that extracted information.

Or, one might say: data >>> information >>> assessment >>> action.

Seabrook also noted that one of the biggest challenges faced by expert systems – though probably also with many other legal tech applications – is the time needed with legal experts. If a system’s value depends on the ability to make expert decisions based on the knowledge of senior lawyers, then those lawyers need to give their billable time to the project. But, because they are top lawyers they are also in most demand, so are least likely to have any free time.

Neota also announced that they will be producing a new, ‘lighter version’ of their expert system, which perhaps will allow lawyers to create short and quicker versions of the very detailed applications the company makes today. That should help drive uptake of expert systems across the legal sector.

Next up was Kira’s CTO, Alexander Hudek, who gave a great demonstration of the AI company’s Quick Study capability and impressively did a live document analysis that the audience could log into and follow along with.

Artificial Lawyer cannot really do justice to reviewing how Kira works in a paragraph, so it’s suggested you have a look at their site and ask if you can try out Quick Study yourself.

Perhaps, the key point in terms of the ICAIL conference that Hudek made is that the number of documents you need to train the system is not always large. In fact, Hudek explained, document training sets of as low as 20 are enough for some types of NLP analysis. In others, where the documents are very diverse and where the targeted information may be highly varied, this can stretch up to 1,000 documents needed to train the system.

That said, the Quick Study demo took less than 30 minutes, and it was impressive to see guided machine learning taking place in front of your eyes and in a way that probably any person could grasp quite quickly.

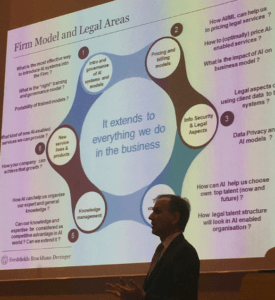

Then we had Milos Kresojevic, Global Innovation Architect at Freshfields, who gave an overview of how his firm saw AI and other legal technologies. His key takeaways were that AI is not about just gaining efficiencies, but creating products that may not have been possible to make before; that law firms need to hire polymaths rather than IT experts, or legal experts, if they want to do well in the changing world, as what mattered was the ability to see the legal landscape with new and evolving perspectives; and that if a law firm was using cloud services with its AI work, then it would have to tell the client in the interests of being transparent about where the client’s data was going.

Finally, we had two more academics, L. Thorne McCarthy, Rutgers University on Semi-Supervised Learning of Legal Semantics, and Kees van Noortwijk from Erasmus School of Law on Automatic Document Classification in Integrated Legal Content Collections.

These were useful additional insights, though didn’t really seem to bridge the gap between the academics and the audience too much. McCarthy’s observations also came across, in Artificial Lawyer’s view, at one stage as overly sceptical about one particular AI company that has done a huge amount of very positive work promoting legal AI technology, though he had praise for some other applications on the market.

And now to the finale. Katie Atkinson, of the University of Liverpool, and President of global IAAIL organisation, which organised the ICAIL event, then sought to tie everything together and search the audience for ways in which academia and lawyers could work more closely together.

This was a valiant and largely successful effort, but what came out of the end of the workshop discussion were the following points:

- That we started off talking about lawyers in commercial law firms and academics, but the ecosystem involved here is much larger and more complex.

- The ecosystem involves: private practice lawyers; inhouse lawyers; people who are not lawyers but make use of legal documents in companies and may also seek AI solutions; law schools; legal AI academics; tech vendors and those forums and media channels that help link all these stakeholders together.

- The reality soon dawned on Artificial Lawyer after listening to the wide variety of questions and points made that perhaps the real challenge we have now is deciding: what are we trying to achieve? For example, if lawyers spend time with academics, what is the end goal? What are these meetings for? Who are they designed to help?

- And, in turn this then introduces some very pragmatic issues, such as who is going to pay for this bridge building? Academics are professionals too, and they need to be paid for their time. Lawyers also need to cover the costs of working on non-billable work. Who will pay?

- Then there was the issue of sharing data. Lawyers would find it hard to share live client data with anyone. Though perhaps actual client matters are not always needed to develop new tech?

- And then there were some who didn’t even accept that lawyers and academics even should be working together and that it made more sense for academics and legal tech companies to combine forces and then in turn help law firms. Though someone then pointed out this created an IP issue, as for example, if a PhD student helps a legal tech company design a new application, then who owns it? A thorny question….

- And, some of the audience also pointed out that if academics’ work didn’t translate into specific use cases that would help law firms to provide a better service to their clients then it was hard to gain engagement in the first place.

- While some also noted that it was hard to criticise academics when law firms were often very secretive about what they did and didn’t want to share anything with outsiders for fear of losing some ‘competitive advantage’. Which in turn generated calls for law firms to work in unison to develop greater understanding of AI and other new technologies, rather as banks have worked together in consortia to develop blockchain technology. So, luckily, we ended on a positive note.

So, what came out of this inaugural attempt to bridge the gap between lawyers and legal AI academics?

Overall, it was a success because it brought people from all over the world together in one place to listen and discuss the use of AI. So that was a good start. Next, it allowed academics to hear what the lawyers and tech co.s were doing. But, it also raised plenty of challenges.

That said, the only way to start solving a problem is to openly lay out all the issues for all to see. Then we can all start to try and find solutions. And, one thing is certain, the room was full of energy and interest and that is a great sign.

The question now is: what happens next? Artificial Lawyer humbly suggests more regular meetings to drive greater engagement, perhaps quarterly, to keep the momentum going. An effort may also need to be made to create more information sharing in an open setting to help foster a more collaborative movement. And, as was suggested by some in the audience, perhaps the way ahead is to create a consortium of law firms that want to work together and also work hand in hand with the academics, all for the greater good. Here’s hoping.

[Artificial Lawyer would also like to say a special thank you to Nick West, CSO of Mishcon de Reya and also again to Katie Atkinson, of Liverpool University, who got this unique workshop off the ground and got the foundations of the bridge well and truly started. And another special mention also goes to UK law firm, Weightmans, which helped sponsor the event.]