Privacy by Design: Building a Privacy Policy People Actually Want to Read

By Richard Mabey, CEO of Juro, the end-to-end contract management platform.

We’ve been banging on about legal design at Juro for some time now. So, when it came to updating our privacy policy ahead of GDPR it was important to us from the get-go that our privacy policy was not simply a compliance exercise. Legal documents should not be written by lawyers for lawyers; they should be useful, engaging and designed for the end user. But it seemed that we weren’t the only ones to think this. When we read the regulations, it turned out the EU agreed.

Article 12 mandates that privacy notices be “concise, transparent, intelligible and easily accessible”. Legal design is not just a nice to have in the context of privacy; it’s actually a regulatory imperative. With this mandate, the team at Juro set out with a simple aim: design a privacy policy that people would actually want to read.

Here’s how we did it.

Step 1: framing the problem

When it comes to privacy notices, the requirements of GDPR are heavy and the consequences of non-compliance enormous (potentially 4% of annual turnover). We knew therefore that there would be an inherent tension between making the policy engaging and readable, and at the same time robust and legally watertight.

Lawyers know that when it comes to legal drafting, it’s much harder to be concise than wordy. Specifically, it’s much harder to be concise and preserve legal meaning than it is to be wordy. But the fact remains. Privacy notices are suffered as downside risk protections or compliance items, rather than embraced as important customer communications at key touchpoints. So how to marry the two.

We decided that the obvious route of striking out words and translating legalese was not enough. We wanted cakeism: how can we have an exceptionally robust privacy policy, preserve legal nuance and actually make it readable?

Step 2: changing the design process

The usual flow of creating a privacy policy is pretty basic: (1) management asks legal to produce privacy policy, (2) legal sends Word version of privacy policy back to management (back and forth ensues), (3) management checks Word doc and sends it on to engineering for implementation, (4) privacy policy goes live.

This is a design process of sorts. It’s just a very bad one. And it typically results in a privacy policy that is the legal equivalent of offering your customer a glass of water and then directing them to a fire hydrant.

We took issue with two things. First, it seems unusual that lawyers are the only people internally with significant input into the process. No marketing, no content editors, no designers. Second, we found that businesses are almost never crunching data on usage of privacy policies or, better, just asking readers of the policy for feedback. The changes under GDPR need attention from legal, but there is a more fundamental design challenge at play.

Rather than the standard process, we decided to start with the end user and work backwards and started a design sprint (more about this here) on our privacy notice with multiple iterations, rapid prototyping and user testing.

Similarly, this was not going to be a process just for lawyers. We put together a multi-disciplinary team co-led by me and, legal information designer Stefania Passera, with input from our legal counsel Adam, Tom (our content editor), Alice (our marketing manager) and Anton (our front-end developer).

Step 3: choosing design patterns

We made too many design decisions in the process to mention here. But here are three that we think made a difference:

Problem 1: general information overload

Solution: layering information

One of the first things we learned was that most users of privacy policies feel overwhelmed by the sheer quantity of information in them. Forget the legalese, forget the small print – quantity alone sends readers to sleep. According to researchers from Carnegie Mellon university, if people actually read all terms and conditions they’ve had to accept in their lifetime, it would take an estimated 76 days. Model that out for privacy notices and it’s a similarly life draining number.

Unfortunately, we couldn’t just strip everything out. There are complex concepts to convey, that GDPR demands you cover in a privacy policy. Instead we opted to preserve all necessary legal nuance and display it in a ‘layered’ approach (which is actually encouraged by GDPR), to serve the needs both of those glancing at their rights and those looking for very specific answers to privacy questions. It had to be adaptable.

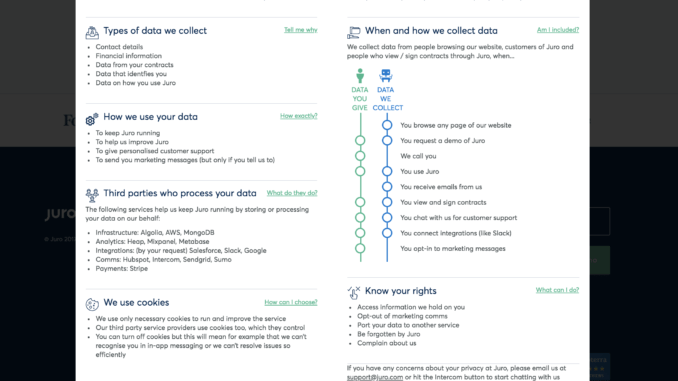

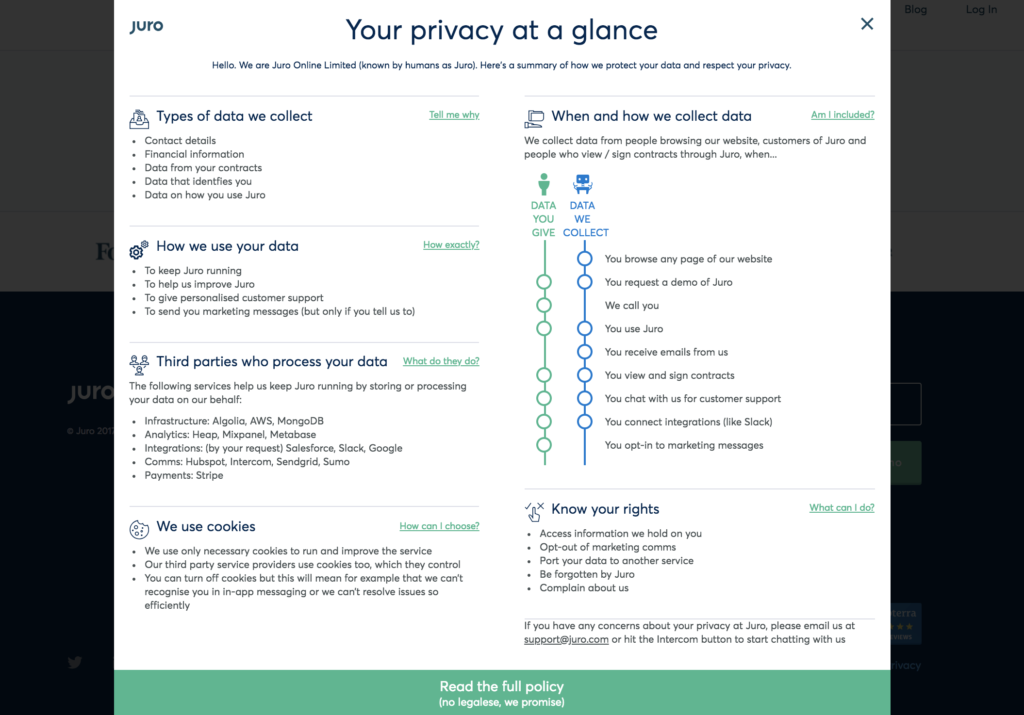

We decided early on that 80% of the information contained in a privacy notice could be conveyed on one page of a typical browser without scrolling. We took the most important information and did just that: a one page pop-up summary of the policy. Simple, up-front, and you can always click through to the full privacy policy if you want more information. Here’s the final privacy summary design:

We applied a similar layering approach in the full privacy policy itself. For the most important items, like choices and rights for data subjects, this all appeared by default. For other items, the user would just click ‘read more’ to see information contained in ‘expandables’. And this layering was not just at the top level. We played around with little ‘tags’ in the policy. For example, where the lawful basis for consent was ‘by contract’, a little tag would be included that would then link to a fuller explanation later down in the policy. We’re still testing how useful these micro layers will be but the early indications are good.

Problem 2: what the hell are you talking about?

Solution: conveying meaning through icons

We soon identified another problem: people often don’t understand the content in privacy policies. Again, no quick fix here. But, Recital 60 of GDPR (well done if you get that far) gave us a gem. It says that privacy communications may be used “in combination with standardised icons”. The ways in which icons can be used is a bit more nuanced than just sticking in icons in a privacy policy, but that’s for another day. The important point for us is that icons are generally permitted forms of communication for the purposes of GDPR, and we could at least include them in the policy.

With this in mind, we built a set of icons that we thought would enhance our customer’s understanding of our privacy notice in both the summary and the full policy.

It was actually fairly easy to find a nice icon set but it was hard to find exactlythe right icon – icons that would genuinely enhance meaning. So we asked people. Typically we showed at least 2 examples of potential icons to user testers and asked them to choose what made the most sense to them (example below). Sometimes these results were decisive and where there was a tie in the number of votes, it just required some judgement from us.

Problem 3: when is my data collected?

Solution: privacy journey diagram

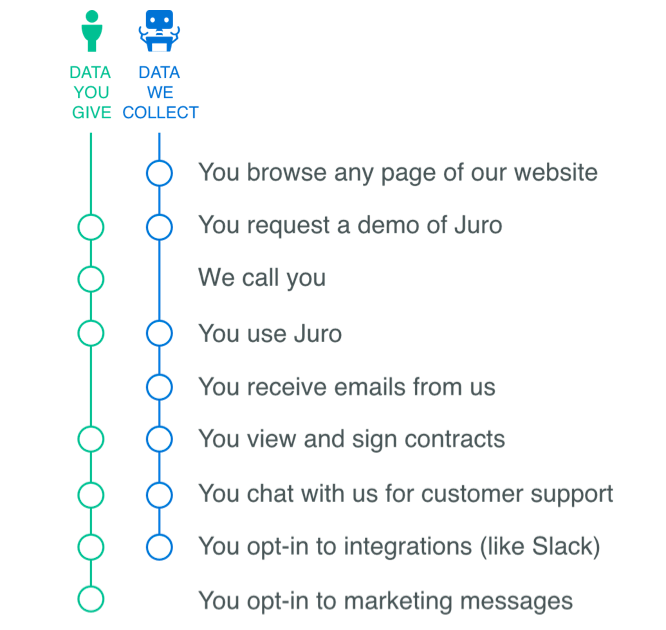

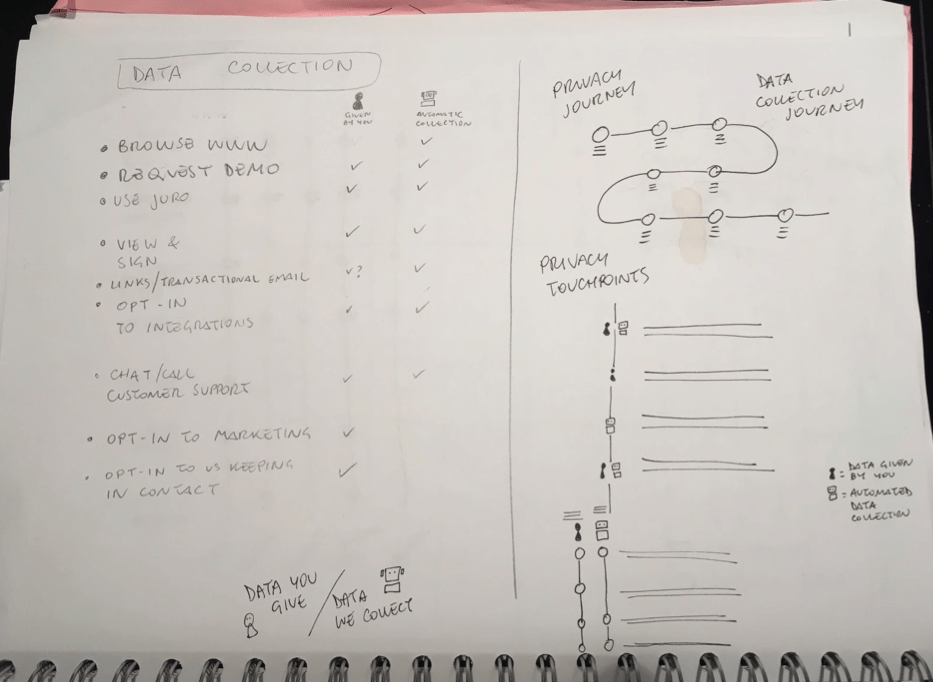

One common concern from our users is that they didn’t feel they had adequate explanation of when, where and how their data was being collected. Sometimes this is data given to us and sometimes this is data collected automatically. Of course, the issue was not that this wasn’t disclosed in our existing privacy policy. It’s just that it was hard to find all this information because of the way in which it was presented: piecemeal, wordy and distributed throughout the document.

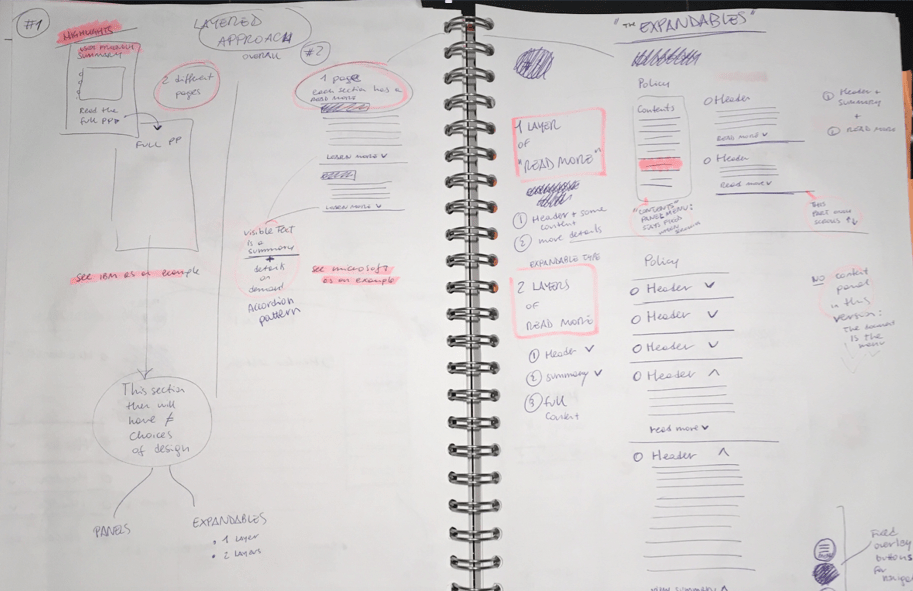

We started reimagining this process of data collection as a ‘privacy journey’, starting with the very first time you land on our website and ending when you leave the Juro service (though we hope this doesn’t often happen) and this informed our choice of design pattern (inspired by Margaret Hagan and Helena Haapio). Here’s an early sketch of our thinking, showing the sequential nature of where data is collected.

The real ‘light bulb’ moment came when we realised that there were in fact two clear tracts of data collection happening in parallel: data that our customers actively give to us and data that is passively collected automatically. If we could show both, could we give a snapshot to our users of what their ‘privacy journey’ with Juro might look like?

This looks like a simple representation but in reality it’s a million miles from the average privacy policy in terms of what it shows in a short amount of time. If we assume the average user stays on a privacy policy for 5 seconds, this might actually give enough meaning to a user to explain which data is collected and when.

Step 4: user testing

The Article 29 working group recently put out guidance around what constitutes transparency. “In advance of ‘going live’, data controllers may wish to trial different modalities by way of user testing (e.g. hall tests) to seek feedback on how accessible, understandable and easy to use the proposed measure is for users”, they say.

They are absolutely right. Getting rapid feedback on your designs is just as important as the sketching and prototyping. As with pretty much any software development work, you really really don’t want to build the wrong thing. We had a programme of user feedback sessions that focused on asking open-ended, unbiased questions about various versions of our privacy policy. We were lucky to have real Juro users volunteer for this (with various degrees of legal knowledge), as well as some legal design experts too (thanks Arianna Rossi).

Some like Marie Pôtel-Saville were both users and legal design experts (bonus!) and she and I are hosting a free webinar on this topic on 18 May (details here).

Step 5: iterate

Doing this well is really hard and we made lots and lots of mistakes. You’ve got to be humble about your assumptions and just try some stuff out (which is something we as lawyers rarely have the luxury of doing). Make no mistake, this is time-consuming work and it can be quite a rabbit hole without good discipline and a clear structure to the process. But rapid prototyping and learning from these mistakes is what can really drive good design outcomes.

We are fortunate to work every day with forward-looking legal teams. Designing a human-centric privacy policy is one very practical and concrete way these teams can build a better legal organisation. Worst case, you comply with your regulatory obligations; best case you help build a world class legal organisation.

Take a look at the privacy policy here and, of course, please do let us know your feedback.

4 Trackbacks / Pingbacks

Comments are closed.