Some weeks ago the CodeX legal tech group at Stanford University in California hosted a conference on the future of law. Peter Darling, CMO of innovative legal email company, Zero, was there and very kindly covered a key session on what autonomous vehicles will mean for the legal world.

—

‘Speakers included Stanford faculty, a researcher from the Google Brain project, a researcher from the University of Technology Sydney and a student from Stanford Law School, Bryan Casey, whose work was particularly interesting.

Casey’s research has studied the public policy implications of the artificial intelligence built into autonomous vehicles as it relates to liability for accidents.

Here are the key insights from the session:

Autonomous Vehicles

- Accident law is a massive area of law.

- Four million accidents per year in the United States alone.

- Compensation for these accidents is defined in formal tort and insurance law

- The scale/complexity of these accidents has forced society to routinize accident liability and compensation. It’s a formula now.

- The formula: Compensation is medical expenses plus property damage plus lost wages

- The use of autonomous vehicles changes all this.

- Once fleets of vehicles are operating autonomously at scale, they’ll be the ultimate repeat players in this

- For a fleet of vehicles, compensation costs for accidents are part of their business model

- A large number of vehicles will unquestionably be involved in a certain number of accidents. Statistically, for example, 500 vehicles which travel a million miles in a year will, statistically, have 45 (or whatever) accidents, with some percentage of them being serious. This is simple probability analysis at work.

-

- This will result in liability, and payouts

- This can be calculated, and affected by the engineering of the vehicle’s onboard artificial intelligence.

- AI is beginning to be constructed based on the optimal risk management of these predicable accidents.

- AV companies are trying to codify risk management law

-

- They look at cumulative costs of all the expected negative outcomes

- Weight costs/benefits

- Decide on optimal policies

- This is a codification of judge Learned Hand’s tort formula

Since Judge Learned Hand first penned the famous algebraic expression, PL > B, that came to bear his name, judges, lawyers, legal scholars and economists have debated its meaning, significance and limitations.

The formula instructs potential tort parties to base their levels of precaution on three variables: (1) the probability, P, that an accident will occur; (2) the magnitude, L, of resulting harm, if any accident occurs, and (3) the cost of precautions, B, that would reduce the expected harm.

Parties are supposed to factor these variables into a comparative benefit-cost analysis, prior to engaging in activities that might result in costly accidents, to determine efficient levels of care.

When the cost of an accident, the monetary cost of harm, L, times its probability of occurring, P exceeds the costs of prevention, B, then the accident should be prevented. When B exceeds PL, however, the accident should not be avoided. Society’s net wealth or welfare is maximized by preventing only those accidents where B is less than PL. Thus, the Learned Hand formula is designed to maximize a social welfare function.

-

- You execute decisions on operations (self-driving cars) based on the lowest risk x magnitude scenario

- An accident with big payouts will influence the risk formula within these cars

- Costs of prevention weighed against costs of liability

Liability calculation includes:

-

-

-

- Likely income of victim

- Vehicle speed changes according to race, age, etc.

- The vehicle doesn’t decide which person to kill, but makes tradeoffs based on large-group statistics

-

-

If we codify our laws into machines, they’re going to take them literally:

-

- Vehicles might, for example, drive more slowly in high-income neighborhoods because the payout in case of an accident is higher than in a lower-income one

- If an accident is inevitable, the vehicle will seek to collide with the beat-up old car rather than the BMW

From an overall social-welfare perspective, this all makes statistical sense. However, it also makes into law some principles people may find upsetting/difficult to live with.

The page for this particular discussion is here.’

Many thanks to Peter Darling at Zero for coverage of this event for Artificial Lawyer. Great to see the world of automation and AI seen through a different perspective, i.e. how lawyers may approach it as a practice area. Also, if you’re interested in using machine learning and automation to improve your use of firm email and help record billable time while working off a mobile device, check out the Zero site, it’s worth a look.

P.S. I found this short video (not part of CodeX) on the famous Learned Hand formula for those not familiar with it. Please see below. It’s particularly interesting as it’s an example of a judge turning to an algorithm (of sorts) to describe a legal outcome – just the kind of thing that AI systems also operate with.

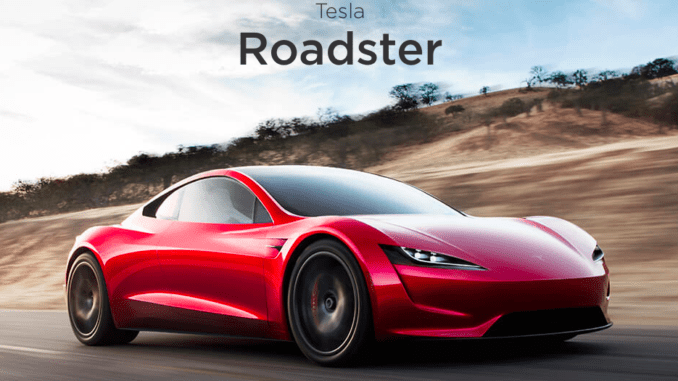

[ N.B. Main Pic credit: Tesla, Inc. ]