In a stunning escalation of the movement against statistical analysis in litigation, the French National Bar Council (Conseil National des Barreaux, or CNB) is now demanding lawyers are also excluded from statistical analysis of their actions in court.

The move follows the news last month that France’s judges had gained for themselves a ban on the use of public court data for the statistical analysis and prediction of their decisions in court. That demand was made law and carries a maximum penalty of five years in prison for those who breach the rule.

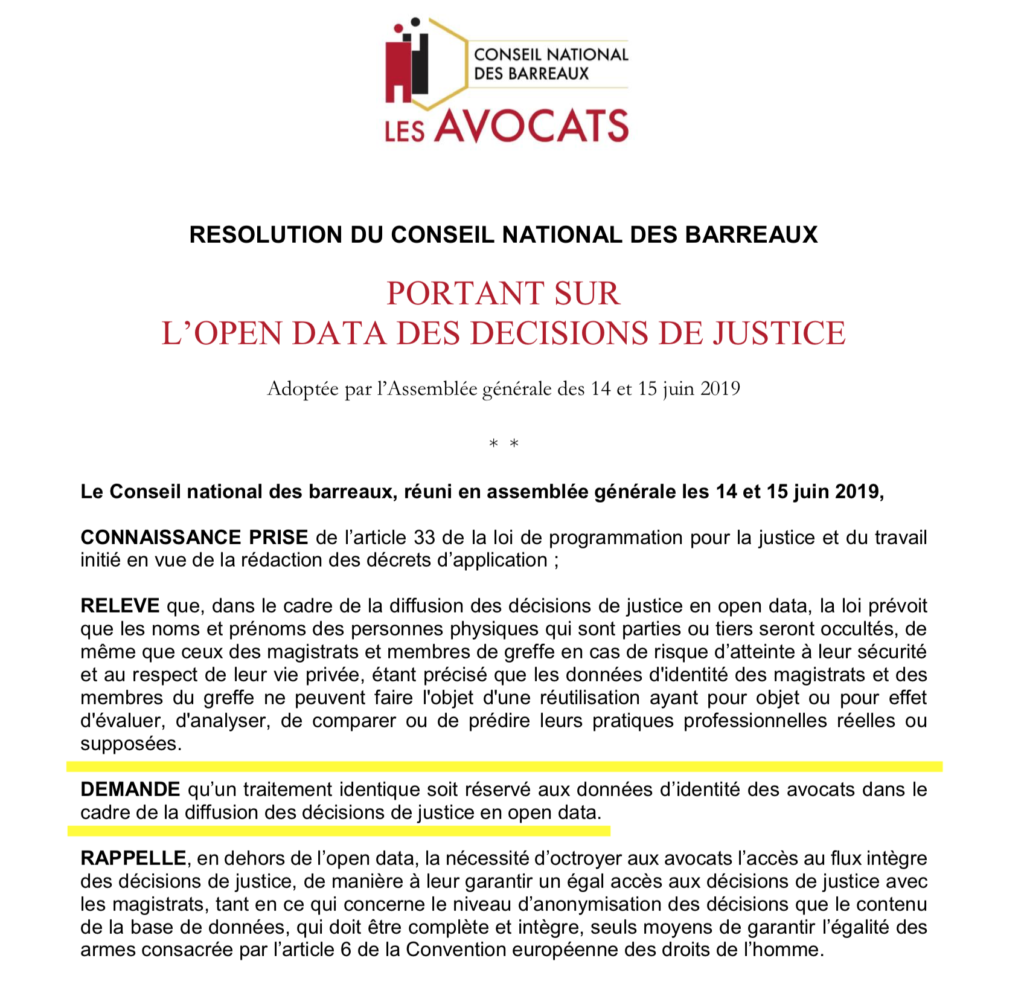

The CNB demand, which was recently voted for, states: ‘[We demand the] identical treatment be reserved for identity data of lawyers in the context of the dissemination of court decisions in open data…it being specified that the identity data of judges and members of the court cannot be reused with the purpose or effect of assessing, analysing, comparing or predicting their actual or perceived professional practices.’

(See full French text below).

Unlike the judges’ new anti-open law position, the trial lawyers’ demands are not yet enshrined in legislation. But, the CNB is understood to be lobbying the Government and French Ministry of Justice to have this equivalent measure made law.

While the CNB has considerable influence over the regulation of lawyers in France it cannot change a rule regarding public data use and so whether it can get this measure through depends on French politicians and senior members of the civil service.

If this were to happen, then we would be looking at potentially the first country in the world where litigation analysis and predictive modelling faced such a comprehensive ban.

In the US, for example, the area of litigation analytics using NLP and ML techniques has become a significant business with large companies (such as LexisNexis) and startups (such as Gavelytics) getting involved in the area. It would be hard to imagine such a move there, although it’s been said that some US judges are sympathetic to the idea of not having their decisions statistically analysed.

In the UK we also already have companies such as Solomonic and CourtQuant, which are conducting predictive analytics on English law cases.

If lawyers do get the ban in France, legal tech companies could still analyse how certain legal arguments played out in court, what claimants could expect to be paid, or how many claims of a certain type usually win, but without the names of the professional parties involved, and without that of the judges’ names either, hence with a lot less granularity and less specific insights.

In effect a barrier would be brought down on what legal professionals do in court, stopping the public from seeing what is happening or being able to gain a better understanding of the patterns taking shape in court.

As with the judges’ data ban, the issue centres around the use of what is now open data and raises the peculiar reality of a country’s citizens being told how they are allowed to use data that is already in the public domain.

Experts in France say the move is all the more surprising as it is understood the CNB held a very different view just three years ago when France first moved ahead with its ‘Open Data’ project to make all public data available online for all to see, including court data.

Antoine Dusséaux, co-founder of Doctrine, an AI-based legal research and litigation analytics company, told Artificial Lawyer: ‘This is a radical change of position from the CNB. Indeed, the CNB has consistently reiterated its position in favour of transparency and open justice over the past three years, and its opposition to the anonymisation of both judges’ and lawyers’ names.’

‘This new position also appears to conflict with the position and interests of most French lawyers. A recent IFOP poll commissioned by Doctrine shows that 87% of French lawyers were against anonymisation of judges’ names, and that 63% of young lawyers wanted to increase their online visibility.’

‘In fact, several lawyers among our customers contacted us to express their shock and strong opposition to the CNB’s motion. They deem it irreconcilable with their mission to represent and defend their clients, which they are proud of and which they want to continue conducting in full transparency,’ he concluded.

–

What Does This Mean?

We are looking at potentially a leading democratic country, a key member of the EU and bastion of progressive ideas, making it a crime to understand the patterns of behaviour in court of its lawyers. If court data was already secret such a move could be understood, but in most cases and especially under the Open Data initiative in France, this court data is already public.

This raises many issues, from how courts should operate, to whether it is even justifiable to have a world where there is a ‘two-tier’ public data system – i.e. where citizens can know some things, but not others, even when the underlying information is public.

One could almost see this as ‘banning the use of mathematics in law’, as the aim is to stop a scientific approach to understanding what judges and lawyers do in court. Fundamentally this could be seen as ‘anti-science’ and anti-open data – all the more remarkable for a country such as France that has done so much to pioneer scientific exploration and human rights.

Will other countries join in? At present, although there is a discussion on the impact of such measures in many legal communities, especially in the US, there appears to be no other country moving in this direction – yet. That said, as one of the most important members of the EU, one could imagine that other European legal markets will certainly be paying attention. Countries with a less open approach to justice may also find these steps quite alluring.

For now, the CNB effort remains a lobbying position and is not law. But, if judges were able to gain this form of censorship then perhaps the trial lawyers will also be able to win this special treatment as well.

–

What do you think? In a world where judges are beyond statistical analysis isn’t it fair to include the trial lawyers under the same law? Or, as explored above, is this taking a potentially dangerous step toward curtailing public access and the understanding of one’s own legal system?

—

CNB Declaration (key section highlighted)

What are they afraid of? This sort of hot denial usually is a cover for some systemic preservation of self-interest in l’ancieme regime and fear of the searing searchlight of facts & data. Premonition has being using predictive analysis for some years now. Hallo France?