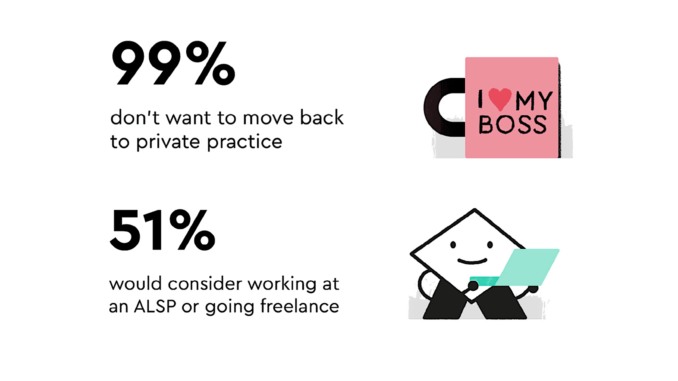

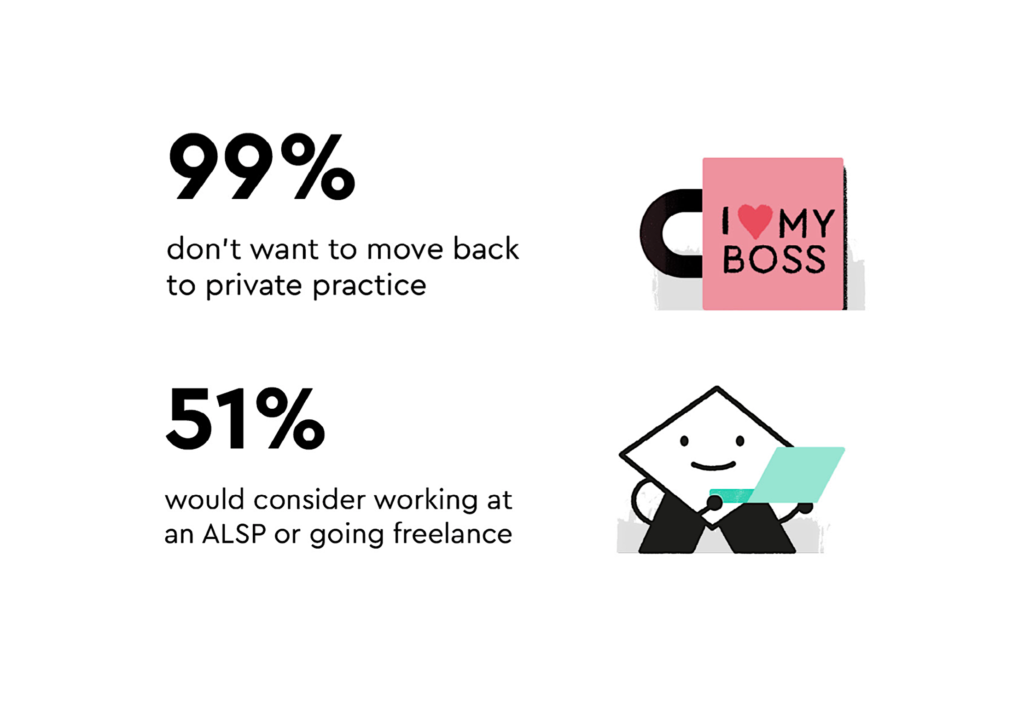

A new survey of inhouse lawyers has found that almost no-one would return to private practice, with just over half of the sample saying that if they were going to leave their inhouse role then they would consider a job at an ALSP, or live a freelance life instead.

The data, gathered by Juro’s latest Tech GC Report, which was backed by US law firm, Wilson Sonsini, confirms what many in the market suspected already: that once you leave the world of law firms and billable hour targets you very rarely ever go back – at least in a fee-earning role.

Interestingly, the opposition to returning to law firm life is despite firms embracing working from home because of the pandemic, with more flexible working likely to be the long-term culture in the future – at least in terms of where the work is done.

That just over half of the sample, which was of 80 inhouse lawyers mostly at tech and fast-growth companies, would consider a move to an ALSP or some kind of ‘lawyers on demand’ lifestyle, is also indicative of how much broader the options now are for a lawyer, with more and more ALSPs of different types springing up.

Several decades ago, the large majority of lawyers were in law firms come what may, then the inhouse world went through an extended – and still continuing – phase of rapid expansion. Now the world of ALSPs and flexible resourcing are growing to maturity as well, offering yet more choice.

From talking to inhouse lawyers over the years it’s clear why they don’t want to go back to life inside a law firm: the hours culture. They liked their colleagues and took a lot of pleasure in being part of a big deal or court case, but the relentless need to keep logging those hours just killed it for many of them.

Others have also told this site about how they decided to leave when they saw several years ahead of what they viewed as highly repetitive work, often using an inefficient manual approach that led to lots of frustration on their part. Although they were very well paid, they could just not imagine doing that even for one more year. (And in fact, several legal tech founders were forged by that experience.)

This is interesting especially in relation to the debate about associate hiring and retention, especially in what remains an ‘up or out’ culture, i.e. you are either on the partnership track (and can survive its many demands), can find a parallel role in professional support/knowledge management or perhaps in a dedicated innovation role, or you leave after a few years of working incredibly long hours on work you have little say over.

Long ago this site did a back of the envelope study on how many associates ever reached equity partner, and came to the broad conclusion it was about 10% of each cohort at most. Perhaps these days it’s even less, perhaps 5%.

In such a world, it is a good thing that there are now more alternatives, (not that all associates want to be partners either).

Changes Inhouse

The survey found that although inhouse lawyers were fairly happy with their lot, (76% said they would prefer to stay in-house), it was not all a bed of roses.

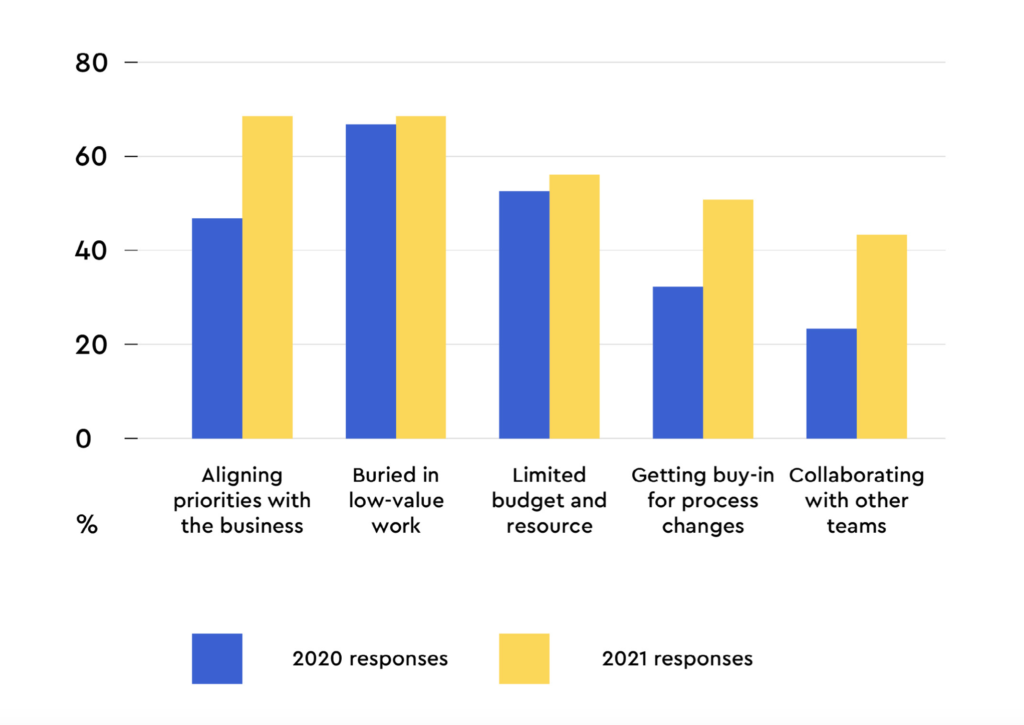

When asked what were the top three concerns they had the inhouse lawyers were partially focused on the same things as last year: having a limited budget and being buried in low value work.

The latter is of course ironic, given the above point made to this site by several people who left law firms that they couldn’t stand the manual monotony of some of their associate work. In fact, around 70% of the sample said that too much low value work was still an issue.

The one point that did really stand out was about getting buy-in for process change, which rose from around 30% to about 50% in one year. Perhaps this means that more inhouse teams are thinking about how they can change work flows and crunch inefficiencies through automation and better contract management?

It also suggests that even if they are focused on this more now, their companies are not, as if they were, presumably those things would get sorted out?

As ever, this suggests an often dysfunctional relationship between inhouse lawyers and their employers. On one hand the C-suite wants the inhouse team to save the company on a daily basis, on the other it wants them to cut costs – albeit without in many cases stopping using the expensive firms they rely upon. At the same time companies remain – it would appear – not totally convinced that the inhouse team needs radical change itself in how it works.

More broadly, and more positively, what did inhouse lawyers like about their lives inside a company? This is what they highlighted:

- ‘Flexibility: “I’m a parent of two small children and my current position works well to accommodate this”

- Influence: “I enjoy being in-house with direct influence and contribution to the business I am in”

- Impact: “the in-house role is very powerful and I enjoy it”

- Potential for growth: “there are still so many exciting things to achieve in my current role”

- Variety: “I’m not interested in spending time with lots of other lawyers – at my job I get to collaborate with different people everyday”

- Challenges and opportunities: “I love the challenge of growing a business from the inside and being part of the mission”

So, things seem pretty good there, even if there are issues around low value work and changing processes.

Low Value Work

On this point about ‘low value’ / monotonous work – which as noted, is a bit ironic given the reasons why some people leave law firms – David Wang , Chief Innovation Officer at Wilson Sonsini, had this to say: ‘When answering the conundrum of why lawyers find themselves buried under low-value work, I think it’s important to emphasise that there’s no correlation between legal work that needs completing and the value of the work.

‘There’s always going to be a high volume of work, and ‘high-value’ work is often wrapped in layers of process that’s hard to untangle. Sometimes you don’t even detect the high-value legal issue because you do not have the resources to handle the low value work needed to “unwrap” the problem.

And that’s the main challenge for GCs at fast-growing, venture-backed companies. The leadership isn’t thinking about risk, but rather about the next funding round and how to scale. Since legal is often under-resourced relative to this quick pace of growth, if it is there at all, you can’t ‘unwrap’ enough of the high-value work to this type of scaling. Therefore, it is primarily an exercise of strategically triaging risk and accumulating a “risk debt,” much like how technical debt works in software development.’

—

You can find the full report, which also quotes from a wide range of experts, here.

1 Trackback / Pingback

Comments are closed.