The New Wave of legal tech has many aspects, from using AI for doc review, litigation prediction, jury selection and billing analysis, to a wide variety of expert systems and legal bots.

But, there is also a growing group of what could be termed ‘end to end contracting automation tools’ or CATs, which are already making an impact among corporates.

This group of new legal tech vendors has not had quite as much coverage as others, perhaps because the ultimate users of CATs are not lawyers, but rather sales executives and other staff who must work with contracts on a daily basis.

While a senior sales exec may not be trained in the law, they understand that the clauses on certain aspects of the sales contracts they form, negotiate and sign are of vital importance to the company and have legal repercussions.

Meanwhile, large companies don’t want to drown their inhouse legal teams in checking the thousands of contracts sales teams can produce. Several legal tech companies have begun to address this issue. One of them is UK-based Avvoka, co-founded by former Slaughter and May associate, Eliot Benzecrit, (other CATs that readers may wish to have a look at include: Synergist.io and also Juro).

Artificial Lawyer spoke to Benzecrit about his start-up and where it is now headed.

Benzecrit explains that their first iteration of Avvoka, which is a play on the French word ‘avocat’, was launched in July last year. The CAT system was trialled by several large companies including asset finance houses, yacht brokerage firms and a major listed property group.

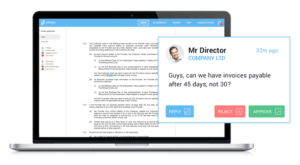

Avvoka’s ability to help executives build up contracts from templates, install ‘legal red lines’ set by the inhouse legal team, and then allow the ‘non-lawyers’ to negotiate and complete the contracts within the system’s digitally set boundaries was a success.

Certain clauses are ‘locked’ and can only be changed by the client’s lawyers, but other aspects can be freely negotiated, at least if within the bounds of the client’s ‘playbook’. This allows rapid and safe contracting to take place without the need for lawyers to continually check what is happening. In turn the lawyers can get on with more value-added tasks.

Now, Avvoka is expanding its capabilities.

‘The aim is to create a type of Google Docs for contracts so that clients can draft live versions of a contract in a structured way and in a way that takes into account the adversarial aspect of negotiation,’ Benzecrit says.

Moreover, the aim is that clients piloting the system will find they are also accumulating a lot of valuable data that relates to how certain aspects of contracts are made. I.e. commercial data, rather than just legal data.

For example, the system is able to collect data on what contractual terms are most successful, or which particular executives are best at negotiating certain parts of a sales contract, or where particular terms were rarely rejected by the other side. In effect, a total picture of the commercial contracting process is provided to the client while also hugely reducing the need for low level legal input. In short, a double win.

As Benzecrit says, the template-to-bounded negotiation capabilities were one thing, but the ability to collect and easily analyse contracting data provides additional value. This is possible because the process is digital, from the first template to the e-signature, with the document never leaving the realm of the client’s data capture.

Now Benzecrit says he also wants to make use of technologies usually associated with AI, such as natural language processing (NLP) and machine learning.

The idea is that by running NLP over the contracts inside the Avvoka system clients can then tag certain clauses to speed up the process of identifying key aspects of a contract

But that is not the end of the story. As with many legal tech companies, Avvoka is finding that as it explores the realm of digitally constructed contracts and the data trail they provide, new ideas come to mind.

One idea that he and others are looking at is how to crystallise some of the data collected on how companies contract to help create the best possible templates.

After all, every time someone uses Avvoka, or another system that can sort the unstructured data of a contract, they are adding more data points to the picture of what is the best contract for that company in that type of matter.

Once a company has learnt this, why not then keep it and re-use that knowledge to make ‘the perfect template’?

Law firms and inhouse teams already work hard on perfecting their templates, and have done so for many years, especially for simpler types of contract. But, with more intelligent systems, especially when using NLP and more advanced data collection on outputs of each clause and how they are negotiated, far greater levels of perfection may be possible in terms of template creation.

In effect, the fast food company has turned its knowledge of process (e.g. making burgers on an industrial scale, but always to the same specifications, then selling them via a limited menu) to the legal process.

But, Benzecrit does not see this steady move of contract automation and digital data capture to create perfect templates as harming the legal profession, quite the opposite in fact.

‘Young people are leaving the legal profession because they have to do boring work and feel unappreciated. With the adoption of Avvoka, hopefully lawyers will be used for more substantive tasks,’ he concludes.

And that sounds like a very positive move for all involved.

2 Trackbacks / Pingbacks

Comments are closed.