Smart contracts that operate via a blockchain have one little problem: you can’t normally use British pounds, dollars or Yen (i.e fiat money), to conduct business with them. Instead you have to use a cryptocurrency, something that not everyone wants to do.

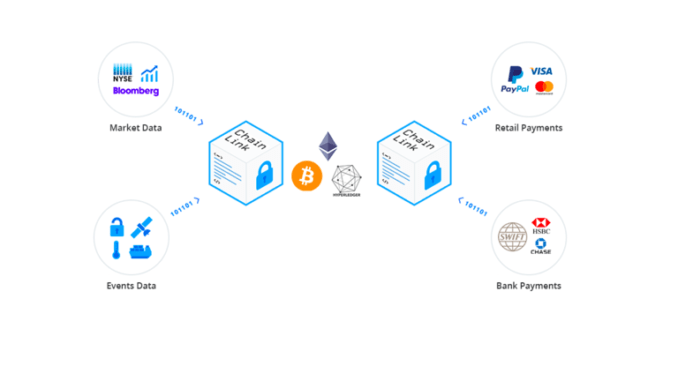

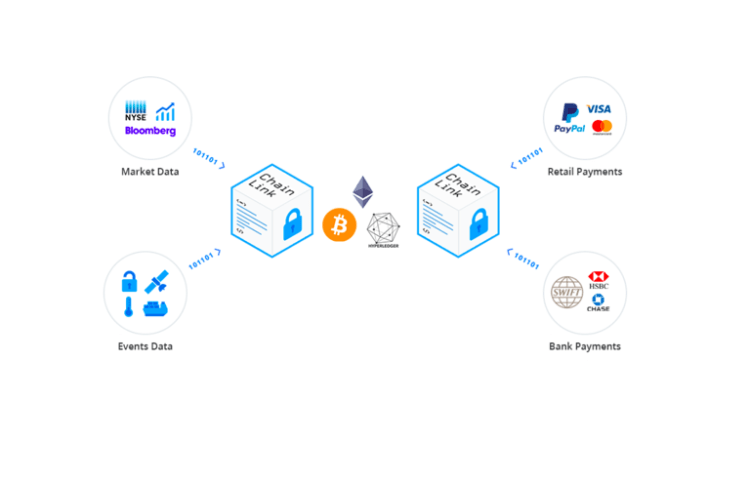

But, ChainLink is working to get around that problem using what the blockchain world calls an ‘oracle’, which is a bridge between the network of nodes that form the blockchain and the outside world. I.e. the nodes may be many, but they are connected to each other, if you have a smart contract operating via this network then you also need something to feed in real world information to drive any actions programmed into the contract.

ChainLink, whose co-founder Sergey Nazarov’s early work was profiled in Artificial Lawyer back in July 2016, has now formed a partnership with smart contract pioneer, OpenLaw, to show how real world fiat currencies can be used easily with self-executing payment clauses in a legal contract.

ChainLink is blockchain middleware that allows smart contracts to access key off-chain resources like data feeds, web APIs, and traditional bank account payments. It has some impressive partners, including the Swift global payments organisation.

Meanwhile, OpenLaw is a blockchain-based protocol for the creation and execution of legal agreements. Using OpenLaw, lawyers can ‘more efficiently engage in transactional work and digitally sign and store legal agreements in a highly secure manner, all while leveraging next generation blockchain-based smart contracts’.

As a first step, blockchain assets (such as cryptocurrencies and tokens) can now be transferred on OpenLaw smart contracts denominated in U.S. dollars.

Then, using ChainLink’s middleware, it can make the transaction in Ether (or ETH), the cryptocurrency used on the Ethereum blockchain.

But, this then creates another problem: cryptoucurrency values are constantly changing, because they are floating currencies, freely traded and subject to the whims of the market, sometimes swinging wildly in value from month to month.

How can you have a smart contract that designates a certain sum of money will be paid each month when the underlying cryptocurrency is experiencing huge changes in value?

ChainLink has used a simple solution to solve this, it checks the exchange rates for Ether at the moment the smart contract’s self-executing contractual code is about to make a US dollar payment. This way, although the total quantity of Ether may change, you are still always getting the same amount of US dollars, as set out in the smart legal contract.

‘This partnership shows a promising way forward to lower those [transactional] barriers and make using cryptocurrency in smart contracts simpler and more intuitive for everyday users,’ said the companies.

You may then well ask: so what? What is the use of this? The answer is that if the majority of the world’s lawyers are to make use of smart contracts, then it’s likely that they will want to use real world currencies that their clients are familiar with in the contracts they write.

Most corporates don’t want, for example, their supplier agreements denominated in cryptos that the owners of the business don’t even own or trade themselves. And that’s not to mention the challenges you could run into as a publicly traded company whose accounts have to be made public and need to be clearly shown in fiat currencies. Would most regulators even accept P&L accounts that used crypto?

And if for example a lawyer draws up an employment contract, the company likely will not want salaries denominated in Ether, or Bitcoin, or any other digital currency, nor will the employee. They’d probably prefer it to be in good old fashioned US dollars, or pounds. Imagine paying someone’s salary when it could suddenly rise in value due to the rapid fluctuations in the currency you use (as seen with cryptos), clearly you’d try to avoid that and use a fiat currency that was (relatively) a lot more stable.

The use of smart contracts and oracles in this way gets over this problem and solves what has been a barrier to wider adoption of the tech.

It’s also another sign that many of the challenges of smart contracts are steadily getting ironed out, with groups such as the Accord Project making great progress, while national projects are also taking shape, such as the one recently covered in Australia.

9 Trackbacks / Pingbacks

Comments are closed.